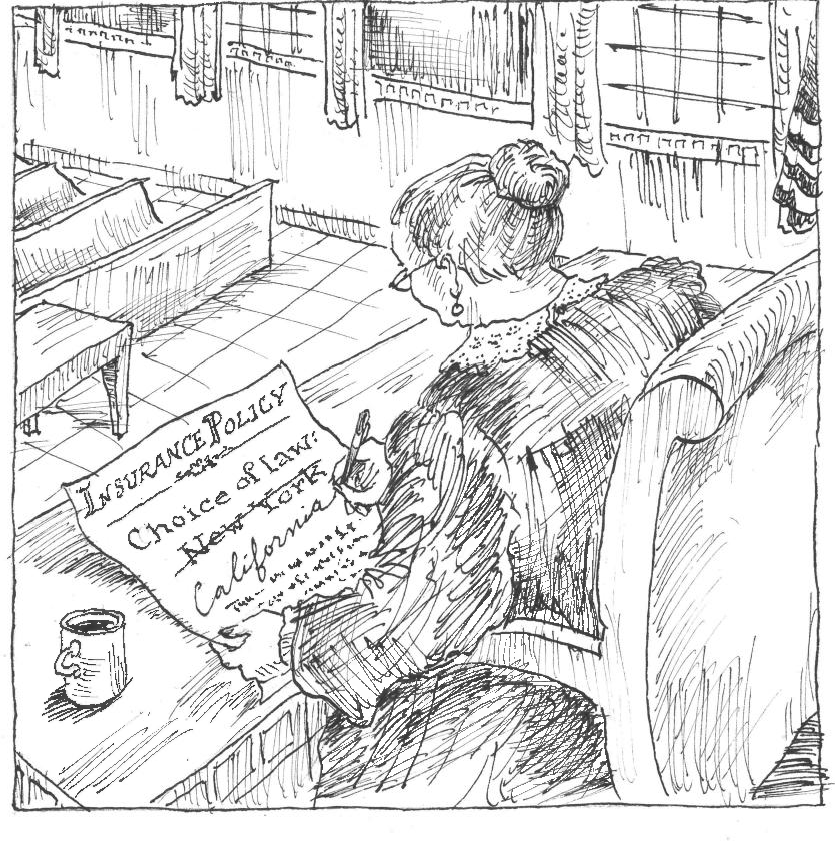

Public policy overrides contractual choice of New York law if California has a materially greater interest in the determination of the coverage issue.

Pitzer College v. Indian Harbor Ins. Co., 447 P.3d 669 (Cal. 2019).

Pitzer College v. Indian Harbor Ins. Co., 779 Fed.Appx. 495 (9th Cir. October 11, 2019).

The “notice-prejudice rule” is a California common law doctrine that “generally allows insureds to proceed with their insurance policy claims even if they give their insurer late notice of a claim, provided that the late notice does not substantially prejudice the insurer.” This distinguishes California law from other states that have adopted a “no prejudice” rule, which conclusively presumes that late notice prejudices the insurer and precludes coverage.

The “notice-prejudice rule” is a California common law doctrine that “generally allows insureds to proceed with their insurance policy claims even if they give their insurer late notice of a claim, provided that the late notice does not substantially prejudice the insurer.” This distinguishes California law from other states that have adopted a “no prejudice” rule, which conclusively presumes that late notice prejudices the insurer and precludes coverage.

In Pitzer, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals certified questions to the California Supreme Court seeking guidance on two issues: (1) whether the notice-prejudice rule is a fundamental public policy of the state that overrides an insurance policy’s designation of the law of another state that does not follow the rule; and (2) whether the rule applies to a provision in a pollution policy requiring the insurer’s consent before the insured incurs remediation expenses.

As to the first question, the California Supreme Court held that the notice-prejudice rule is a fundamental public policy of California law. The rule overrides principles of freedom of contract by favoring “compensation of insureds over technical forfeiture,” and “protect[ing] the public from bearing the costs of harm that an insurance policy purports to cover.” Accordingly, under California choice-of-law principles, a court must disregard an insurance policy’s choice-of-law provision if the designated law does not apply the notice-prejudice rule and California has a “materially greater interest in the determination of the issue than the contractually chosen state.”

With respect to the second question, the Court held that the notice-prejudice rule applies to the insured’s failure to comply with a policy provision requiring it to obtain the insurer’s consent before incurring pollution-related expenses covered by the policy. As with other notice requirements, the failure to obtain consent will excuse coverage if it prejudices the insurer by “meaningfully increas[ing]” remediation costs or hampering the insurer’s subrogation rights.” But the insurer is precluded from obtaining what the Court deemed a windfall in the event the insured’s failure to obtain consent causes no harm to the insurer. The Court noted an important limitation on the rule, however. With respect to third-party policies, prejudice is presumed because consent is necessary to protect the insurer’s “paramount” right to control the defense and settlement of claims.

The dispute in this case arose under an insurance policy that Pitzer College purchased from Indian Harbor covering legal and remediation expenses resulting from pollution conditions discovered during the policy period. The policy contained two relevant provisions implicating the questions certified by the Ninth Circuit: (i) a provision requiring Pitzer to obtain Indian Harbor’s consent before incurring any pollution-related expenses; and (ii) a choice-of-law clause providing that New York law governed any dispute concerning coverage. While New York has a statutory notice-prejudice rule (N.Y. Ins. L. 3420(a)(5)), it only applies to policies issued or delivered in New York. As Pitzer’s policy was neither issued nor delivered in New York, the policy was governed by New York common law, which imposes a strict no-prejudice rule, setting up a conflict between New York and California law.

While the California Supreme Court’s answers to the certified questions may seem straightforward, their application to these facts was not. Indian Harbor argued that prejudice was presumed because the policy provided third-party coverage, given that remediation expenses are a form of legal liability under environmental laws. Pitzer, on the other hand, argued that it provided first-party coverage because coverage is triggered by the insured’s own discovery of the happening of an event, rather than a claim by a third party. The California Supreme Court left it to the Ninth Circuit to apply the answers it provided to the certified questions applied to these facts.

The Ninth Circuit, in turn, remanded to the district court to determine: (1) whether California had a materially greater interest than New York in determining the coverage issue, in which case California’s notice-prejudice rule would apply; (2) if California law applied, whether the policy provided first- or third-party coverage; and (3) if the policy provided first-party coverage, whether the insurer suffered any prejudice from Pitzer’s delayed notice, which would justify the denial of coverage.

Read the court’s full decision here.

“Securities Claim” does not include claims for breach of fiduciary duty, unlawful payment of dividends, or fraudulent transfer.

In re Verizon Ins. Coverage Appeals, — A.3d –, 2019 WL 5616263 (Del. Oct. 31, 2019).

In Verizon, the Delaware Supreme Court addressed whether claims by a spun-off corporate subsidiary against its director and its former parent company for breach of fiduciary duty, unlawful payment of dividends, and fraudulent transfer were covered “Securities Claims” under an executive and organizational liability policy.

The underlying claims at issue arose following Verizon’s divestiture and spinoff of certain businesses into a company called Idearc. After Idearc entered bankruptcy, its trustee sued Verizon and Idearc’s director, alleging violations of fraudulent transfer statutes, payment of unlawful dividends in violation of Delaware General Corporation Law, and common-law claims for breach of fiduciary duty and promoter liability. Although Verizon and the director prevailed in the litigation, Verizon incurred $48 million in defense costs defending itself and the director. Verizon sought coverage for these defense costs.

The policy defined “Securities Claims” as those “[a]lleging a violation of any federal, state, local or foreign regulation, rule or statute regulating securities (including, but not limited to, the purchase or sale or offer or solicitation of an offer to purchase or sell securities).” The Court held that, as a matter of law, the claims at issue did not fall within the definition of “Securities Claims.” Such claims were limited to those alleging violations of laws, rules, or regulations specifically directed toward securities.

None of the claims at issue met that test. The fiduciary duty claims involved common-law duties rather than regulations, rules, or statutes specifically focused on actions involving securities. The claims for unlawful distribution of dividends involved statutes regulating the payment of dividends to protect against the payments resulting in insolvency. The fraudulent transfer statutes were designed to prevent debtors from moving assets (whether or not securities) beyond the reach of creditors. Because these claims were not “Securities Claims,” the policies did not cover Verizon’s defense costs.

Read the court’s full decision here.

Exclusion barred all claims for asbestos exposure in the course of employment, regardless of whether claimant was employed by the insured.

R.T. Vanderbilt Co., Inc. v. Hartford Accident & Indem. Co., 216 A.3d 629 (Conn. 2019).

In a decision addressing a “question of first impression nationally,” the Connecticut Supreme Court decided whether a policy exclusion barring liability coverage for “occupational diseases” precludes coverage claims for injury arising from exposure to asbestos in talc and silica products in the course of employment if the claimant was not employed by the insured.

The insured, R.T. Vanderbilt Company, mined and sold talc and silica. Thousands of individuals sued Vanderbilt for injuries allegedly caused by exposure to asbestos in Vanderbilt’s talc and silica between 1948 and 2008. Vanderbilt sought coverage from its primary and excess CGL carriers who issued policies during the period of exposure.

Two of Vanderbilt’s policies, to which several other policies followed form, contained an exclusion for liability arising from “occupational diseases.” Neither policy defined the term “occupational disease.”

Relying on workers compensation statutes, Vanderbilt argued that ‘“occupational disease’ is a term of art that refers only to disputes between [the] employer and [the] employee or to statutory compensation plans for employees.” According to Vanderbilt, the exclusion therefore did not bar claims by individuals who suffered occupational diseases while working for other employers. Although the trial court agreed, the appellate court reversed. The Supreme Court affirmed.

The Court held that the term “occupational disease” had to be given its ordinary meaning, as reflected in dictionaries contemporary to the 1970s and 1980s when the policies were issued. Per these sources, the ordinary meaning of “occupational disease” was an injury sustained in the course of employment and caused by factors arising from the employment. While the term may have also had a meaning in the workers compensation context, it was not devoid of meaning outside that context, and the exclusions here did not reflect an intent to limit their application to the workers compensation context. On the other hand, the inclusion of other policy exclusions for workers compensation claims and employer’s liability demonstrated that “when the drafters of the policy desired to limit the application of an exclusion to a certain group of individuals, they did so.” This rendered “all the more unambiguous the lack of any such express limitation in the occupational disease exclusions.” Although the exclusion was broad, “the breadth of” the exclusions did not render them “any less clear and unambiguous.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

Only policy in place at the time of the wrongful conduct is triggered, even if the tort of malicious prosecution is completed during the period of a later policy in place when the claimant is ultimately exonerated.

Sanders v. Illinois Union Ins. Co., — N.E.3d –, 2019 IL 124565 (Ill. Nov. 21, 2019).

Sanders was convicted of murder in 1995 based on evidence doctored by Chicago Heights police officers in 1994. In 2011, his conviction was overturned. Sanders’s 2013 retrial ended in a mistrial, and he was acquitted after a third trial in 2014. Sanders settled his malicious prosecution case against Chicago Heights with the city and its insurer under its policy covering 1994. The city and its prior insurer paid $5 million, and the city assigned Sanders its rights under the Illinois Union policies in place from 2011 through 2014.

Illinois Union denied Sanders’s claim for coverage, taking the position that the malicious prosecution did not trigger its policies because it occurred prior to the policy period. The trial court granted Illinois Union’s motion to dismiss, but the appellate court reversed. The Illinois Supreme Court reversed, reinstating the trial court’s decision.

Illinois Union’s policies covered “a Claim arising out of an Occurrence happening during the Policy Period … for … Personal Injury … taking place during the Policy Period” (emphasis in original). The policy defined “Personal Injury” as one or more “offenses,” including “malicious prosecution.” The policy also provided that “[a]ll damages arising out of substantially the same Personal Injury regardless of frequency, repetition, the number or kind of offenses, or number of claimants, will be considered as arising out of one Occurrence.”

The Court held, as a matter of law, that for purposes of coverage under the policy the “offense” of malicious prosecution occurred when the wrongful conduct underlying the claim took place. In Sanders’s case, the offensive conduct was the Chicago Heights police doctoring evidence to incriminate him, before his initial trial. The Court differentiated the “offense” of malicious prosecution under the policy from the tort of malicious prosecution, which is not completed until the victim is ultimately exonerated. The Court found that reference to the tort law definition of malicious prosecution was inconsistent with the policy language and structure. The occurrence-based coverage provided under the policies was not intended to cover acts committed years before the policies commenced.

The Court also rejected Sanders’s argument that his two later trials constituted separate offenses triggering coverage under the later polices. Under the policies’ noncumulation clause, all three trials constituted part of the same “personal injury” because they all arose from the city’s initial doctoring of the evidence. Accordingly, there was only one “occurrence,” which took place at the time of the offense in 1994, prior to the Illinois Union policy periods.

This blog post is a service to our clients and friends. It is designed only to give general information on the developments actually covered. It is not intended to be a comprehensive summary of recent developments in the law, treat exhaustively the subjects covered, provide legal advice, or render a legal opinion.

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.