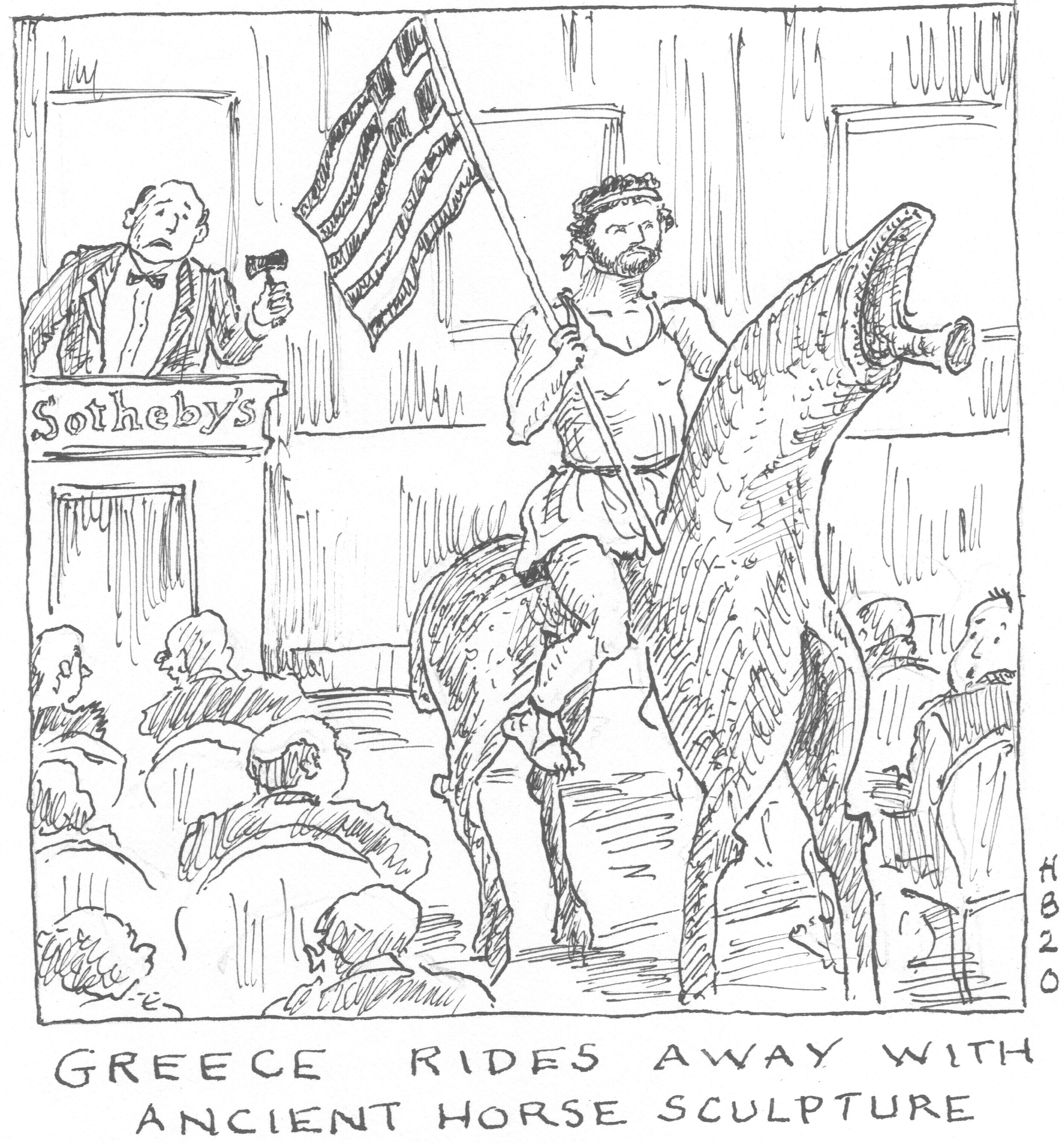

Second Circuit: Greece held immune from suit over ownership of ancient bronze horse figurine; country’s enforcement of its patrimony laws deemed sovereign, not commercial, activity.

Barnet v. Ministry of Culture & Sports of the Hellenic Republic, 961 F.3d 193 (2d Cir. 2020).

In the United States, the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (“FSIA”) provides the sole basis for obtaining jurisdiction over a foreign state. Under the Act, a foreign state is generally immune from suit in U.S. courts, subject to certain exceptions. The most significant of these is the “commercial activity” exception, which authorizes suit against a foreign state that undertakes “an act in connection . . . with a commercial activity of the foreign state” abroad “that act causes a direct effect in the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(2).

In the United States, the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (“FSIA”) provides the sole basis for obtaining jurisdiction over a foreign state. Under the Act, a foreign state is generally immune from suit in U.S. courts, subject to certain exceptions. The most significant of these is the “commercial activity” exception, which authorizes suit against a foreign state that undertakes “an act in connection . . . with a commercial activity of the foreign state” abroad “that act causes a direct effect in the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(2).

The Second Circuit dismissed a declaratory judgment action against Greece in a dispute over ownership of a 2,700-year-old bronze horse figurine sculpture, ruling that the Greek government’s transmission of a letter to the auction house Sotheby’s in New York did not confer jurisdiction under the commercial activity exception. Upon learning that the sculpture was set for auction, the Greek government notified Sotheby’s in an emailed letter that the figurine belonged to Greece under the country’s 1932 Antiquities Act and a more recent statute enacted in 2002. Sotheby’s responded by withdrawing the figurine from its auction but, in an unusual move, filed suit against the Greek government in the Southern District of New York seeking a declaration of ownership.

Greece moved to dismiss the action on sovereign immunity grounds. In opposition, Sotheby’s argued that Greece’s act of sending the demand letter constituted a commercial activity under the FSIA. The district court agreed with Sotheby’s and denied Greece’s motion to dismiss. It reasoned that Greece’s act of transmitting the letter was commercial (rather than sovereign) because private parties likewise “send letters claiming ownership of historical artifacts.”

But a unanimous Second Circuit panel reversed. As it explained, the principal flaw in the lower court’s reasoning was its failure to “appreciate that Greece’s act of sending its letter was connected to the sovereign activity of claiming ownership through nationalization and enforcement of patrimony laws.” Greece was not “compet[ing] in the marketplace like a private antiquities dealer” but rather was enforcing its laws forbidding commercial trade in artifacts like the figurine. The panel explained that, while “a private party might be able to send a letter disputing ownership of an object, no private party could nationalize historical artifacts and regulate the export and ownership of those nationalized artifacts.” Focusing on Greece’s assertion of ownership in isolation, the judges cautioned, “would allow the exception to swallow the rule of presumptive sovereign immunity codified in the FSIA.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

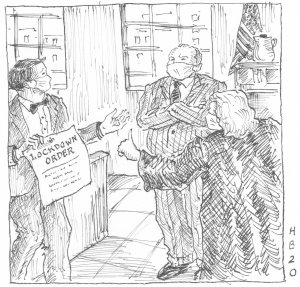

Southern District of New York: business interruption insurance does not cover lost income resulting from government-mandated closures during COVID-19 pandemic.

Social Life Magazine, Inc. v. Sentinel Insurance Co. Ltd., No. 20-cv-3311 (VEC), 2020 WL 2904834 (S.D.N.Y. May 14, 2020).

New York has long recognized freedom of contract as paramount. This guiding principle also applies to insurance policies under New York law: where policy provisions are clear and unambiguous, courts must give the contract language its plain and ordinary meaning and cannot rewrite the parties’ agreement.

New York has long recognized freedom of contract as paramount. This guiding principle also applies to insurance policies under New York law: where policy provisions are clear and unambiguous, courts must give the contract language its plain and ordinary meaning and cannot rewrite the parties’ agreement.

A federal court in the Southern District of New York recently applied these principles to a business interruption claim arising from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In one of the first decisions to weigh in on this issue, the court denied a New York-based magazine publisher’s motion for a preliminary injunction compelling its insurer to indemnify it under a property insurance policy for financial losses resulting from the government-ordered closure of most New York businesses during the pandemic.

The publisher emphasized the absence of a common exclusion for viral pandemics and sought to analogize COVID-19 to hazards such as mold and spores, asserting that “the coronavirus, which is able to attach to surfaces, can indeed cause physical damage to its office building and equipment.” But the insurer countered that the policy language covered only business interruptions “caused by direct physical loss of or physical damage to property” (and not for other reasons). Therefore, the insurer maintained, the publisher could not demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits because it could not show any actual contamination of its property with COVID-19.

After conducting a telephonic hearing, the court denied the injunction. It reasoned that COVID-19 “damages lungs. It doesn’t damage printing presses.” Mold damage, the court explained, is not analogous to an insured’s inability to “use [its] premises because there is a virus that is running amuck in the community.” The judge emphasized that while she sympathized with the insured’s plight, the lack of coverage was clear: “I feel bad for every small business that is having difficulties during this period of time. But New York law is clear that this kind of business interruption needs some damage to the property” in order to confer coverage.

Read the court’s full decision here.

Second Circuit: Credit cardholders could not be compelled to arbitrate dispute over banks’ alleged violations of bankruptcy court orders discharging their debts.

Belton v. GE Capital Retail Bank (In re Belton), 961 F.3d 612 (2d Cir. 2020).

In the United States, the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”) requires courts to strictly enforce agreements to arbitrate disputes. A limited exception to this rule exists where the party resisting arbitration demonstrates that the dispute is not arbitrable because another controlling federal statute evidences a congressional intent to displace the FAA.

At issue in this putative class action on behalf of thousands of credit cardholders was the relationship between the FAA and the United States Bankruptcy Code. The plaintiff cardholders alleged that, even after the bankruptcy court discharged their credit card debts at the conclusion of Chapter 7 liquidation proceedings, the defendant banks refused to update their credit reports to reflect the discharge. Instead, the reports continued to identify the debts as “charged off” (that is, severely delinquent). The cardholders argued that the banks’ refusal amounted to an attempt “to coerce [them] into repaying” the discharged debts. On that basis, and “purporting to represent a nationwide class of similarly situated debtors,” the named plaintiffs “reopened their bankruptcy cases and initiated adversary proceedings against the [b]anks” seeking to hold them in contempt.

This was not the first time the Second Circuit was asked to consider the arbitrability of bankruptcy court discharge orders. In a similar case two years earlier, a different Second Circuit panel held “that Congress did not intend for disputes over the violation of a discharge order to be arbitrable.” Without identifying a textual basis in the Bankruptcy Code evidencing that congressional intent, the previous panel based its decision on the statutory purpose, reasoning that “the discharge injunction is ‘integral’ to the bankruptcy process.” The banks now argued that the court was no longer bound by the prior panel’s decision because an intervening 2018 decision by the United States Supreme Court in a case called Epic Systems had undermined its reasoning. They maintained that Epic Systems “rejected the notion that an inherent conflict between statutory purpose and arbitration is independently sufficient to displace the Arbitration Act.”

But the panel disagreed. While noting that, “[i]f we were writing on a blank slate, perhaps our conclusion would be different,” it held that it was “bound to affirm” the lower court’s judgment that the parties’ dispute was not arbitrable. As the court explained, while Epic Systems “describes an exacting gauntlet through which a party must run to demonstrate congressional intent to displace the Arbitration Act,” it did not alter the rule that “an ‘inherent conflict’ is sufficient to displace the Arbitration Act where the statutory text is ambiguous.” However, the court made clear that this result should not be seen as a “tacit endorsement” of the cardholders’ theory that “a nationwide class action is a permissible vehicle for adjudicating thousands of contempt proceedings.” Instead, the court left the issue of class certification for resolution “another day.”

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.