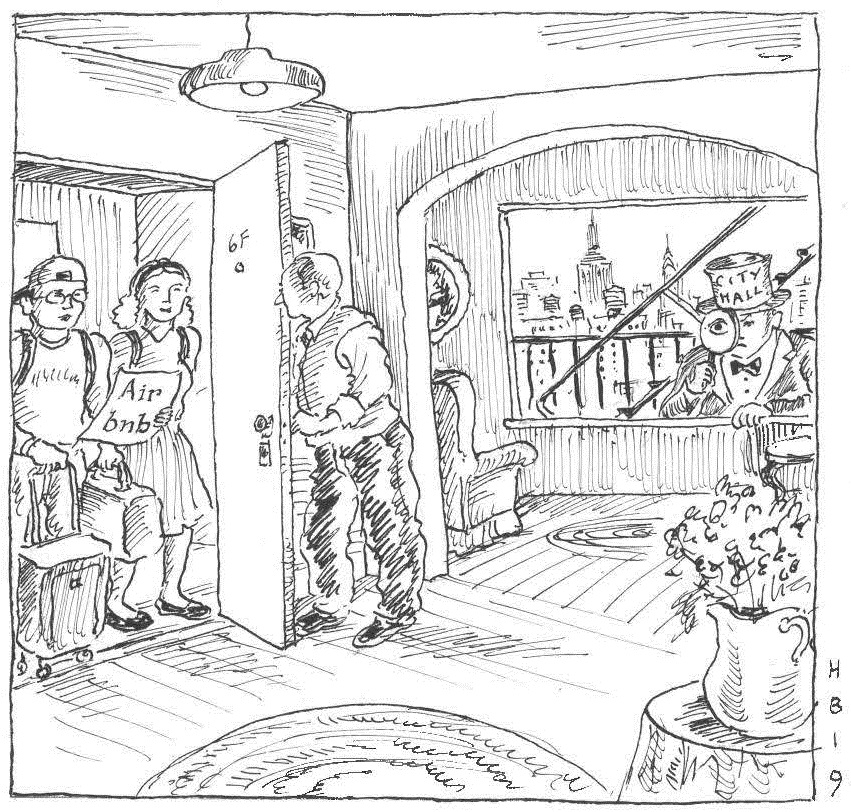

Southern District of New York: AirBnB and HomeAway win preliminary injunction against New York City’s crackdown on short-term rental operators.

Airbnb, Inc. v. City of New York/ Homeaway.com, Inc. v. City of New York, No. 18-CV-7712 (PAE)/ 18-CV-7742 (PAE), 2019 WL 91990 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 3, 2019).

In January, a federal judge in the Southern District of New York blocked New York City’s recent legislative attempt to crack down on short-term rental companies like AirBnB. The court found that a City ordinance requiring such companies to produce large amounts of user data to the City was likely unconstitutional. The ruling illustrates the factors courts consider when deciding whether to grant a preliminary injunction (i.e., a court order that restrains a party from a course of conduct and preserves the status quo until the court can decide the case).

In January, a federal judge in the Southern District of New York blocked New York City’s recent legislative attempt to crack down on short-term rental companies like AirBnB. The court found that a City ordinance requiring such companies to produce large amounts of user data to the City was likely unconstitutional. The ruling illustrates the factors courts consider when deciding whether to grant a preliminary injunction (i.e., a court order that restrains a party from a course of conduct and preserves the status quo until the court can decide the case).

A preliminary injunction can be a powerful tool at the outset of a case but is subject to strict requirements. First, the applicant must persuade the court that it faces a “substantial chance” of “irreparable harm” absent injunctive relief. Second, the applicant must show a likelihood (though not a certainty) of success on the merits. Third, the court must balance the harm each party will suffer if it grants the injunction to determine whether “the balance of hardships” tips in the favor of the party seeking the injunction. Fourth, and finally, courts must ensure that the preliminary injunction “serves the public interest.”

Plaintiffs Airbnb and HomeAway challenged the enforcement of a New York City ordinance requiring short-term rental companies to report information about rental units and the hosts who list them to the Mayor’s Office of Special Enforcement. Plaintiffs argued that enforcement of the ordinance would violate their constitutional right under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to freedom from unreasonable search or seizure. The court agreed, finding that plaintiffs had satisfied the preliminary injunction standard. The court first found that plaintiffs were likely to succeed on the merits. The court was concerned that the ordinance would “permit regulators to troll these records for potential violations of law.” But the Fourth Amendment does not permit “such a wholesale regulatory appropriation of a company’s user database.”

The other elements followed. The court found that the threatened constitutional violation (which would recur monthly) would cause plaintiffs irreparable harm. On the balance of hardships, the court concluded that the threatened irreparable harm to plaintiffs outweighed any harm to the city resulting from delayed enforcement of the ordinance if the court ultimately deemed it constitutional. Finally, although the public has an interest in protection from the harms of short-term rentals, the court held that the city could police such rentals through other measures. The city has appealed the decision to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

New York Court of Appeals: New York law bars contracting parties from agreeing in advance to defer the accrual of future contract claims.

Deutsche Bank National Trust Company v. Flagstar Capital Markets, 32 N.Y.3d 139 (Oct. 16, 2018).

New York’s public policies favoring freedom of contract and the enforcement of statutory limitations periods clashed in this recent decision by New York’s highest court, the Court of Appeals. At issue was whether an “accrual clause” in an agreement for the sale of residential mortgage-backed securities could extend the time for the plaintiff to bring suit. In a 7-2 decision, the Court of Appeals gave greater weight to the public policy favoring clear limitations periods and restricted contracting parties’ ability to defer the accrual of claims under New York law.

Deutsche Bank (the purchaser of the securities) sued for breach of the seller’s representations and warranties seven years after the mortgage loans were originated. The parties’ agreement provided that “[a]ny cause of action . . . arising out of the breach of any representations and warranties . . . shall accrue . . . upon (i) the discovery of such breach by the Purchaser, (ii) failure by the Seller to cure such breach . . . and (iii) demand upon the Seller by the Purchaser for compliance with this Agreement.” Deutsche Bank argued that New York’s six-year statute of limitations did not bar its breach of warranty claim because this accrual clause created a substantive condition precedent to suit, such that “the statute of limitations [wa]s not triggered until” the conditions specified in the accrual clause were satisfied. Alternatively, Deutsche Bank asserted that the clause manifested the parties’ clear intent to extend the statute of limitations.

The Court of Appeals rejected both arguments and affirmed the lower courts’ dismissal of Deutsche Bank’s claims. First, the Court held that the accrual clause did not create a substantive condition precedent to the accrual of the breach of warranty claim. Under New York General Obligations Law § 17-103, an agreement to extend the statute of limitations must be made after the cause of action accrues and may extend the limitations period, at most, for the statutory “time period that would apply if the cause of action had accrued on the date of the agreement” (e.g., six years for a breach of contract claim). The Court explained that under Deutsche Bank’s interpretation, the accrual clause would constitute a prohibited agreement to “extend the limitations period . . . made before a breach of contract cause of action had accrued” and for an indefinite period, since “plaintiff’s discovery of the breach or defendant’s notice of the breach might occur decades into the future, for the life of the mortgage loans.”

The Court then analyzed the conflicting public policies favoring freedom of contract on the one hand, and the enforcement of statutes of limitations on the other. Deutsche Bank argued that the public policy favoring freedom to contract permitted the parties to agree to extend the statute of limitations even before a claim accrues. But the Court of Appeals disagreed, holding that “contracting parties may . . . agree to a shorter limitations period,” but “public policy restricts their ability to make an agreement extending the statutory period before a claim accrues.”

Two judges strongly dissented. Judge Rivera argued that “enforcement of the accrual provision is wholly aligned with the public policies animating both the freedom to contract and our statute of limitations.” Judge Wilson agreed and warned that the majority had set a bad precedent that may compel parties to “choose the law of some other state because New York considers these agreements against a public policy supposedly undergirding limitations periods.”

Read the Court’s full decision here.

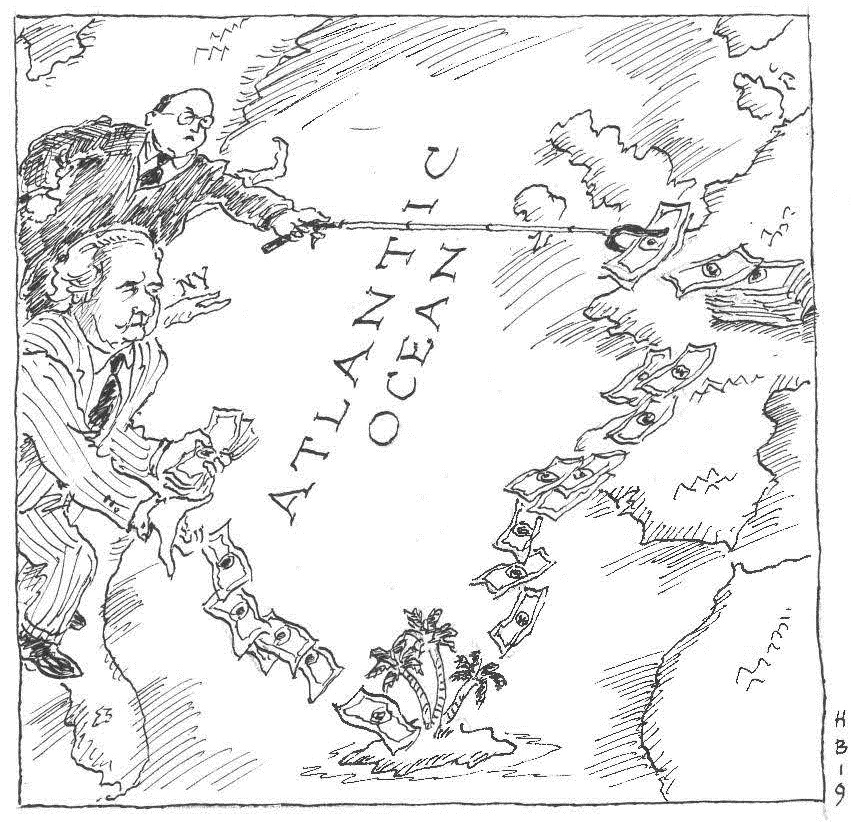

Second Circuit: Presumption against extraterritorial application of federal statutes did not preclude Madoff trustee’s claw-back claims against foreign feeder fund investors.

In re Picard, 917 F.3d 85 (2d. Cir. Feb. 25, 2019).

U.S. federal statutes generally apply only to activity within the United States unless Congress clearly expresses its intent for a particular statute to apply extraterritorially. The harder question the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decided in this high-profile case arising from the collapse of the Madoff Ponzi scheme is what to do when a statute does not expressly provide for extraterritorial application, but its application to a particular set of facts will have an extraterritorial impact.

U.S. federal statutes generally apply only to activity within the United States unless Congress clearly expresses its intent for a particular statute to apply extraterritorially. The harder question the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decided in this high-profile case arising from the collapse of the Madoff Ponzi scheme is what to do when a statute does not expressly provide for extraterritorial application, but its application to a particular set of facts will have an extraterritorial impact.

In that circumstance, courts examine where the activity on which the statute focuses took place. Applying this test, a three-judge Second Circuit panel held that neither the presumption against extraterritoriality nor principles of international comity prohibited the Madoff bankruptcy trustee from recovering assets from foreign entities—even where those entities were more than one step removed from the Madoff bankruptcy estate in the United States.

Many of the investors in Madoff’s fraudulent investment firm, Madoff Securities, were so-called “feeder funds.” As the court explained, “[a] feeder fund is an entity that pools money from numerous investors and then places it into a ‘master fund’ on their behalf.” The “master fund” in this case was Madoff’s Ponzi scheme. When a feeder fund investor withdraws funds, the withdrawal occurs in two steps: “The master fund [first] transfers the money to the feeder fund (the initial transfer), which subsequently transfers the money to its investor (the subsequent transfer).” Because many of the Madoff feeder funds and their investors were foreign, the issue before the Second Circuit was whether the Madoff trustee’s claims for recovery of assets from foreign feeder fund investors violated the presumption against the extraterritorial application of U.S. law and the principles of international comity.

The trustee’s claims against the feeder fund investors arose under section 550(a)(2) of the Bankruptcy Code, which authorizes the recovery or claw-back of property from subsequent transferees in certain circumstances, including where the transfer is deemed fraudulent and is therefore “avoidable” ( i.e., voidable). Analyzing the statute, the Second Circuit held that the relevant transaction was not the subsequent transfer to foreign investors, but the initial transfer from Madoff’s U.S. “master fund” to the feeder funds. On that basis, the court found that the statute’s “focus” in this case was on U.S. activity. Therefore, the trustee could recover property “regardless of where any initial or subsequent transferee is located.”

The Second Circuit likewise held that considerations of international comity did not hinder the trustee’s attempt to recover assets. In general, international comity allows courts in their discretion to decline jurisdiction over an international case or to limit the international reach of a statute. The court held that “[t]he United States has a compelling interest in allowing domestic estates to recover fraudulently transferred property.” On the other hand, because Madoff Securities was in liquidation in the United States, the court characterized the interests of the foreign jurisdictions where the feeder funds were based (and where they are now in liquidation) as “not compelling.” Finally, the court held that the application of U.S. law would not unfairly surprise the foreign feeder fund investors: “When these investors chose to buy into feeder funds that placed all or substantially all of their assets with Madoff Securities, they knew where their money was going.”

This blog post is a service to our clients and friends. It is designed only to give general information on the developments actually covered. It is not intended to be a comprehensive summary of recent developments in the law, treat exhaustively the subjects covered, provide legal advice, or render a legal opinion.

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.