Our hearing opened normally on March 9 , with both sides’ fact witnesses and party representatives, as well as one of the arbitrators, having traveled to New York from abroad. Because none of the fact witnesses was a native English speaker, translators were also on hand. The plan was to complete fact witnesses in the first week and expert witnesses in the second. While COVID-19 was in the news, we did not yet foresee any difficulty in completing the hearing on schedule. Indeed, we planned to share a good New York steak dinner with our client and team after the final day, two weeks hence.

How wrong we were!

Over the course of that first week concern about COVID-19 grew daily. Nonetheless, we still didn’t imagine the scope of what was coming and remained determined through the week to forge ahead and complete the hearing as planned. However, by Friday of the first week the potential for adjournment was clearly there. By Sunday it became reality, as the parties and witnesses were called home ahead of impending travel restrictions. Everyone who had been with us in New York that week returned to two weeks of self-quarantine in their home countries.

Not very long ago, that would have thrown the case into an open-ended limbo. Leaving aside the uncertain duration of the COVID-19 crisis, it would likely have been many months before we could find a an open week for all participants. Fortunately, our tribunal was committed to avoiding that outcome. It recognized that in the circumstances, meeting by video would become the “new normal,” if the technology was ready. The tribunal directed the parties to meet and confer and, if possible, come back by Wednesday of what would have been week two of the hearing with a technical and procedural protocol for resuming by video. Counsel for both sides worked together to make this happen.

The Challenge

The requirements seemed steep. We needed a system that would allow up to 40 individuals to participate or observe. Everyone had to have a clear view of the tribunal, the witnesses and examining counsel. All participants had to be able to read the expert PowerPoint presentations and the numerous exhibits to be used in cross-examination. We also required that the tribunal and counsel continue receiving individual feeds of the LiveNote transcript.

In any event, the technical solution proved to be much simpler than anyone expected. Although we had been using Zoom and similar products for some time, we had not fully appreciated their full capabilities. We also had been used to doing video conferences with professional video equipment from our office conference rooms. With that experience, we initially contemplated that participants would use their firms’ conference facilities or go to commercial videoconference centers in each of the relevant cities. That approach proved to be both unfeasible – as offices around the world were closing – and out of date.

The Solution

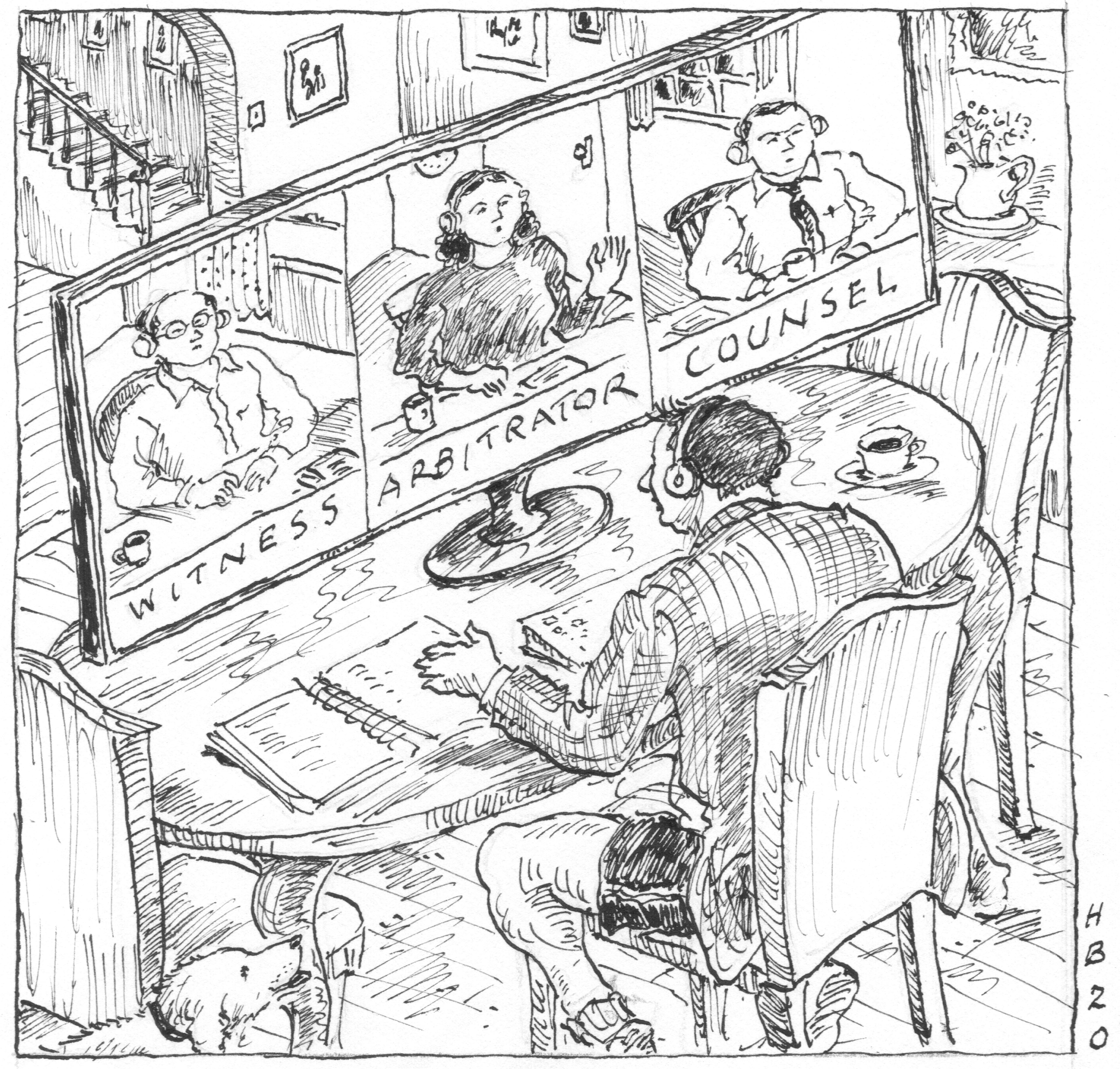

Instead, like so many others during these past days, we quickly became familiar with how robust modern videoconferencing applications have become. In our case we chose to work with Zoom, which under our firm’s license can support a video conference of unlimited duration with up to 100 participants. Within a short time, all involved learned to choose between “gallery view” which displays all participants in thumbnail-sized windows, and the self-explanatory “speaker view.” By asking non-speakers to silence their microphones and stop their video feed, we could limit the video display to the person speaking or to selected participants. Once the hearing got under way, we generally had the tribunal members, the witness, and the examining attorney on the screen. The remaining participants, usually between 30 and 40, could observe quietly.

By selecting the “share screen” function, the expert witnesses were able to present their PowerPoint slides while remaining visible in a separate window to the right of the screen. As needed, the arbitrators and attorneys could also come on view alongside the shared document. During cross-examination, a trial support person took over the “share screen” function to display and highlight documents, portions of witness statements and the hearing transcript that were the subject of the questioning. That worked exactly as in an in-person hearing.

The court reporter listened in as a participant and transmitted her real-time transcript via a software application called “LiveLitigation,” which has long been in use in the United States for video depositions.

The Videoconference Meeting Rooms

Our firm set up the virtual hearing venue as a permanent Zoom meeting room for the duration of the hearing. We provided the necessary credentials to all participants, who were then free to enter or leave the room at any time over the course of the week. Just as in an in-person hearing, the tribunal and each of the parties also maintained separate “breakout rooms” where they could confer privately among themselves.

On Friday, March 20, exactly one week after we had last met in person, we reconvened with the tribunal, opposing counsel, and the court reporter on video for a “technical rehearsal,” just to make sure the system would work and to give the arbitrators and counsel a chance to become familiar with the pertinent Zoom features. For that test run, there were well over 30 participants, all joining from their own homes, in three different countries and four time zones. We found the sound and picture quality to be excellent. After a few minutes, we knew we could resume on Monday and finish our hearing.

What We Used at Home

While we had done individual witness examinations by video or telephone, this was our first experience with a full-blown video hearing. It was also our first time presenting and cross-examining witnesses with limited, and in some cases, no paper documents. This also was not as difficult as expected. For us, the ideal personal set-up involved three devices with screens plus a mobile phone. We used an iPad to work with documents uploaded to PDF Pro. This allows the creation of virtual examination binders in which you can mark up and highlight documents just as you would with paper. We participated in the hearing through our main computer or laptop, and then received the transcript on a third device. A person with a large enough monitor could display the hearing and transcript in separate windows on one screen. No doubt other approaches would work equally well. While Zoom has a “chat” function, it only allows the choice of sending your message to a single participant or everyone. For that reason, and to avoid mishaps, our lawyers team used our phones to keep a private group chat open on which we could confer among ourselves as we were listening. This was a big improvement over trading post-it notes at the counsels’ table.

Examination Notebooks, Real and Unreal

The one throwback to our old ways was the parties’ agreement to provide physical cross-examination binders to the expert witnesses. One of the arbitrators also asked to receive physical binders. Fortunately, our vendor was still available to produce and deliver the binders. We agreed for these to be delivered in a sealed package to the witnesses no less than one hour before their cross-examination was scheduled to begin. We instructed the witnesses that they should only unwrap their notebook on camera at the start of their examination. We also agreed to exchange these files electronically with opposing counsel within 45 minutes of the start of cross-examination, on the understanding that there would be no discussion of their contents with the witnesses. Our protocol also specified that anyone in the room with the witness be visible at all times. That rule proved moot, however, because every participant joined individually from their home or office.

Final Impressions

The hearing wrapped up on Friday, March 27, only a week later than planned. Over the course of five days seven experts made presentations and submitted to cross examination. There were also three “hot-tubbing” sessions where experts for both sides answered questions from the tribunal. The hearing days ran on the same schedule as when we had been meeting in person and ran with equal efficiency. Weekend and evening preparation sessions with the witnesses also worked very well by video.

It was clear from the informal parting exchanges that everyone thought the video format had been a success, with little or no disadvantage compared to the in-person meeting at which we had started. The parties have also agreed to hold closing arguments by Zoom.

Nonetheless, we can’t yet conclude that video offers full equivalence.

As noted, all of our percipient witnesses testified in person in the first week. We don’t know whether the tribunal could have assessed the credibility of such evidence just as effectively by video. Also, it was probably easier to meet by video following an entire week of being together in a conventional hearing. Moreover, it was only in the first week that we required simultaneous translation. Because all of our second week testimony was in English, we did not face the additional challenge of adding separate language feeds to a video hearing. We can also foresee logistical issues where participants are based in more divergent time zones. In our case most participants were on Eastern Daylight Time. The maximum time difference from that time zone was three hours and that affected only a single participant.

It is still less than three weeks since we learned we would be completing our case by video. Given the exigent circumstances, we did not have time to canvass the literature or discuss the merits of the 2018 Seoul Protocol on Videoconferencing in International Arbitration. Our approach was ad hoc and guided by common sense.

Nonetheless, the decisions we made and the arrangement we landed proved to be largely consistent with that guidance. Overall, this was a good and memorable experience that opened our eyes to how far video meeting capabilities have evolved. We do not predict that video will replace in person hearings when normal times return, but we also think this alternative approach will see far greater use.

Peter Chaffetz is a founding partner of Chaffetz Lindsey. Yasmine Lahlou and Andrew Poplinger are partners at Chaffetz Lindsey.

View this article on the New York State Bar Association website.

Click here to view our full list of COVID-19 Information and Resources.