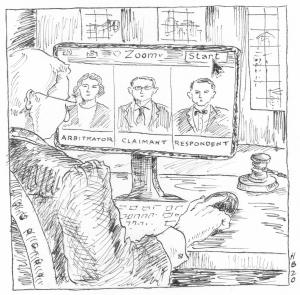

Arbitrators, rather than court, should decide procedural question of whether to hold remote hearing due to Covid-19 pandemic.

Legaspy v. Fin. Indus. Regulatory Auth., Inc., No. 20 C 4700, 2020 WL 4696818 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 13, 2020).

Legaspy appears to be the first U.S. court case during the Covid-19 pandemic addressing an application to enjoin a remote arbitration hearing. In February of 2019, two of Carlos Legaspy’s clients initiated an arbitration against him under the rules of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) to recover nearly $3 million for brokerage account losses. Pursuant to FINRA’s rules, the parties signed a uniform submission agreement which provided that “in the event a hearing is necessary, such hearing shall be held at a time and place as may be designated by the Director of FINRA” and that “the arbitration will be conducted in accordance with the FINRA Code of Arbitration Procedure.” An evidentiary hearing was originally set for August 17, 2020 in Boca Raton, Florida. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, FINRA canceled the in-person hearing and the arbitral panel subsequently ordered that the hearing be conducted remotely via Zoom. Legaspy objected, arguing that a Zoom hearing was unworkable because of the complexity of the issues, the large number of witnesses and documentary exhibits, and the claimants’ need for a translator. After the tribunal overruled Legaspy’s objections, Legaspy filed suit in federal court to enjoin the virtual hearing on the grounds that it breached the parties’ uniform submission agreement and FINRA’s Code of Arbitration Procedure and denied Legaspy due process under the Fifth Amendment. The court denied Legaspy’s motions for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction, allowing the virtual arbitration to proceed.

Legaspy appears to be the first U.S. court case during the Covid-19 pandemic addressing an application to enjoin a remote arbitration hearing. In February of 2019, two of Carlos Legaspy’s clients initiated an arbitration against him under the rules of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) to recover nearly $3 million for brokerage account losses. Pursuant to FINRA’s rules, the parties signed a uniform submission agreement which provided that “in the event a hearing is necessary, such hearing shall be held at a time and place as may be designated by the Director of FINRA” and that “the arbitration will be conducted in accordance with the FINRA Code of Arbitration Procedure.” An evidentiary hearing was originally set for August 17, 2020 in Boca Raton, Florida. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, FINRA canceled the in-person hearing and the arbitral panel subsequently ordered that the hearing be conducted remotely via Zoom. Legaspy objected, arguing that a Zoom hearing was unworkable because of the complexity of the issues, the large number of witnesses and documentary exhibits, and the claimants’ need for a translator. After the tribunal overruled Legaspy’s objections, Legaspy filed suit in federal court to enjoin the virtual hearing on the grounds that it breached the parties’ uniform submission agreement and FINRA’s Code of Arbitration Procedure and denied Legaspy due process under the Fifth Amendment. The court denied Legaspy’s motions for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction, allowing the virtual arbitration to proceed.

The court held that a preliminary injunction was unwarranted because neither Legaspy’s breach of contract claim nor his constitutional claim was likely to succeed on the merits. The court held in the first instance that Legaspy could not state a claim against FINRA for breach of the uniform submission agreement because FINRA was not a party to that agreement. The court further held that Legaspy could not succeed on his claim for breach of the submission agreement or the FINRA Code of Arbitration because, under the Federal Arbitration Act, procedural questions are committed to the arbitrator and “[w]hether FINRA can or should conduct a hearing remotely is a question of procedure that FINRA, not this court, must decide.” Finally, the court determined that even if it could review the arbitral panel’s procedural ruling mid-arbitration, the FINRA Code of Arbitration permitted the panel to order a virtual hearing.

The court likewise found that Legaspy’s claim that a remote hearing would deny him due process was unlikely to succeed because the Fifth Amendment protects citizens from state action (i.e., government conduct) and FINRA is a private corporation, not a state actor.

Read the court’s full decision here.

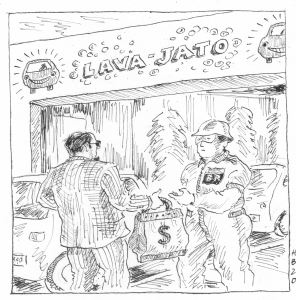

Court must defer to arbitrators’ conclusion that alleged bribery did not invalidate the parties’ contract.

Vantage Deepwater Co. v. Petrobras Am., Inc., 966 F.3d 361 (5th Cir. 2020).

Article V(2)(b) of the Panama Convention, like its New York Convention counterpart, allows an enforcing court to refuse to recognize or enforce an award that “would be contrary to the public policy of that country.” In Vantage Deepwater, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit addressed how the arbitrators’ determination regarding whether the underlying contract was procured through bribery impacts a challenge to the award on public policy grounds. The court held that while the ultimate determination of whether an award violates public policy is for the enforcing court, the court must make its determination on the facts as found by the arbitrator.

Article V(2)(b) of the Panama Convention, like its New York Convention counterpart, allows an enforcing court to refuse to recognize or enforce an award that “would be contrary to the public policy of that country.” In Vantage Deepwater, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit addressed how the arbitrators’ determination regarding whether the underlying contract was procured through bribery impacts a challenge to the award on public policy grounds. The court held that while the ultimate determination of whether an award violates public policy is for the enforcing court, the court must make its determination on the facts as found by the arbitrator.

In 2009, Vantage Deepwater entered into a contract with Petrobras—the Agreement for the Provision of Drilling Services (“DSA”)—to perform offshore drilling services for an eight-year term, which began in 2012. In 2013, after a Brazilian magazine published an article alleging that a Vantage shareholder had paid a large bribe to secure the DSA, Petrobras opened an investigation into the matter. Nevertheless, a few months later, the parties executed a novation and amendment of the DSA in which they reaffirmed that the contract was binding and enforceable. The parties executed a similar novation and amendment in 2014.

In 2015, Petrobas terminated the DSA, claiming that Vantage had materially breached the contract and, additionally, that the DSA was invalid because it was procured through bribery. By the time of Petrobras’s termination, Vantage’s agent in Brazil had pled guilty to bribery in connection with the DSA, which formed part of the larger Lava Jato bribery scandal, which concerned Petrobras executives allegedly accepting bribes in return for awarding contracts to construction firms at inflated prices.

Following a two-week evidentiary hearing, the tribunal, over a dissent, ruled that Petrobas had wrongfully terminated the DSA and awarded Vantage over $700 million in damages and interest. The tribunal found both that Petrobras had not proved that Vantage was guilty of bribery and that Petrobras had, in any event, ratified the DSA by executing the novations and amendments with knowledge of the alleged bribery.

In response to Vantage’s petition to confirm the award in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas, Petrobras argued, among other grounds, that enforcement of the award would violate United States public policy because it would require Petrobras to pay damages on a contract illegally procured through bribery.

The Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s holding that enforcing the award would not violate public policy because the tribunal had found that Petrobras had ratified the contract. The Fifth Circuit explained that, although “courts are the ultimate arbiters of public policy, not arbitrators,” the court must “take the facts as found by the arbitrator” in reaching that legal conclusion.

The court noted that Petrobras was not arguing that the award itself violated public policy, because, for example, it was procured by fraud. Rather, Petrobras was asking the court to determine whether the underlying contract, the DSA, violated public policy. The court explained that the public policy exception cannot be used to question the merits of an award, especially where, as here, the parties’ arbitration agreement granted the arbitrators the authority to rule on the validity and enforceability of the DSA. Whether the DSA should be voided because of bribery is a question of the contract’s validity. Thus, while bribery does violate public policy, whether bribery provided a basis to deny enforcement of the contract at issue was a question for the arbitrators. The arbitrators’ findings that Petrobras waived any bribery objection by ratifying the DSA and that Vantage was, in any event, not aware of the alleged bribery “were within the tribunal’s authority to rule on the DSA’s validity. As such, the validity of the DSA was rightly a question for the arbitrators rather than the district court.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

Tribunal in arbitration between Russian investor and Republic of Lithuania is “foreign or international tribunal” under 28 U.S.C. § 1782.

In re Application of Fund for Prot. of Inv’r Rights in Foreign States pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1782 for an Order Granting Leave to Obtain Discovery for Use in a Foreign Proceeding, No. 19 MISC. 401 (AT), 2020 WL 5026586 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 25, 2020).

28 U.S.C. § 1782 permits a federal court to grant discovery to be taken “for use in a proceeding in a foreign or international tribunal.” A split has emerged among federal circuit courts of appeal over whether § 1782 discovery is available in aid of foreign commercial arbitration. The Second and Fifth Circuits, joined last month by the Seventh Circuit, have held that § 1782 discovery is not available in connection with foreign private arbitrations because they are not proceedings before “a foreign or international tribunal,” as that term is used in the statute. The Fourth and Sixth Circuits, on the other hand, have held that private arbitral tribunals are “tribunals” within the meaning of the statute. (See Volume 1 (Nov. 2019) reporting on Abdul Latif Jameel Transp. Co. v. FedEx Corp., 939 F.3d 710 (6th Cir. 2019)). In this case, the Southern District of New York (SDNY) was called upon to decide whether a tribunal in an arbitration instituted against a state pursuant to a bilateral investment treaty constitutes “a foreign or international tribunal” under § 1782.

In 2019, the Fund for Protection of Investor Rights in Foreign States (the Fund), a Russian corporation, initiated arbitration against the Republic of Lithuania pursuant to the Lithuania-Russian Federation Bilateral Investment Treaty of 2004. The Fund is the assignee of claims by the former controlling Russian shareholder of a Lithuanian bank nationalized by Lithuania. The Fund applied under 28 U.S.C. § 1782 to take discovery from Simon Freakley, a former administrator of the bank appointed by the Lithuanian government, and his firm, AlixPartners LLP. On July 8, 2020, the court granted the Fund’s application.

On the same day, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, whose decisions bind federal courts in New York, decided In Re Guo, 965 F.3d 96, 100 (2d Cir. 2020), which reaffirmed its 20-year old decision in National Broadcasting Co. v. Bear Stearns & Co., 165 F.3d 184 (2d Cir. 1999) that § 1782 discovery is not available for private international commercial arbitrations.

In light of the Second Circuit’s ruling in Guo, Freakley and AlixPartners moved for reconsideration of the SDNY court’s decision. The court denied the motion and upheld its prior decision permitting the discovery. Following the Second Circuit’s recognition in National Broadcasting of the distinction between tribunals in commercial arbitrations from tribunals constituted pursuant to international treaties, the SDNY court sustained its conclusion that the investment treaty arbitration was taking place before a “foreign or international tribunal” within the meaning of § 1782. Specifically, the court noted that the investor-state tribunal “does not ‘possess[] the functional attributes most commonly associated with private arbitration.” This is because bilateral investment arbitration is “a tool of international relations, . . . the Tribunal derives its jurisdiction from the Treaty, and . . . the Arbitration is a means by which [the Fund is] bringing claims against the Republic of Lithuania in its capacity as a state.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

The FAA provides for vacatur of award as exclusive remedy for arbitrator bias.

Texas Brine Co., L.L.C. v. Am. Arbitration Ass’n, Inc., 955 F.3d 482 (5th Cir. 2020).

Plaintiff Texas Brine was a party to an arbitration administered by the American Arbitration Association (“AAA”) seated in New Orleans, Louisiana. During the course of the arbitration, Texas Brine discovered that two of the three members of the arbitral panel had what it believed to be disqualifying conflicts of interest. The AAA’s Administrative Review Council, however, summarily denied Texas Brine’s disqualification motions. Shortly after that denial, the AAA removed one of the arbitrators on different grounds and the remaining two arbitrators resigned.

Texas Brine then moved in Louisiana state court to vacate the arbitral panel’s interim awards. The state court vacated the panel’s rulings pursuant to 9 U.S.C. § 10(a)(2), the provision of the Federal Arbitration Act or FAA which permits a court to vacate an award for “evident partiality or corruption in the arbitrators.”

Following the vacatur ruling, Texas Brine filed a lawsuit against the AAA and the two allegedly compromised arbitrators seeking $12 million in damages and equitable relief. The AAA removed the case to federal court. The federal district court dismissed Texas Brine’s claims on two alternative grounds: (1) the defendants enjoyed arbitral immunity and (2) the Federal Arbitration Act provides the exclusive remedy for complaints concerning an arbitrator’s bias or other corrupt conduct. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision that the FAA was the plaintiff’s exclusive-remedy and declined to “opine on the legitimacy of arbitral immunity.”

The Fifth Circuit held that Texas Brine’s lawsuit constituted an impermissible “collateral attack”—that is, a challenge to an award outside of the exclusive grounds provided in the FAA—on the now-vacated arbitration award. The appellate court explained that there are limited statutory grounds on which a court may vacate a domestic arbitral award and that purportedly independent claims outside of these grounds are not a basis for challenge if they are “disguised collateral attacks on the arbitration award.” To determine whether a plaintiff’s claims constitute a collateral attack, the court examines “the relationship between the alleged wrongdoing, purported harm, and arbitration award.” Applying this test, the court first found that the alleged wrongdoing—the arbitrators’ conflicts of interest—could clearly be remedied by vacatur under Section 10 of the FAA. Next, the court found that Texas Brine’s alleged harm—strategic disadvantage and a tainted arbitration—could likewise be remedied under Section 10. Finally, the court held that Texas Brine’s requested relief for reimbursement of the fees and costs it paid in furtherance of the tainted arbitration were premised on the same infirmity in the proceedings, and therefore did not transform its challenge from a collateral attack into an independent claim.

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.