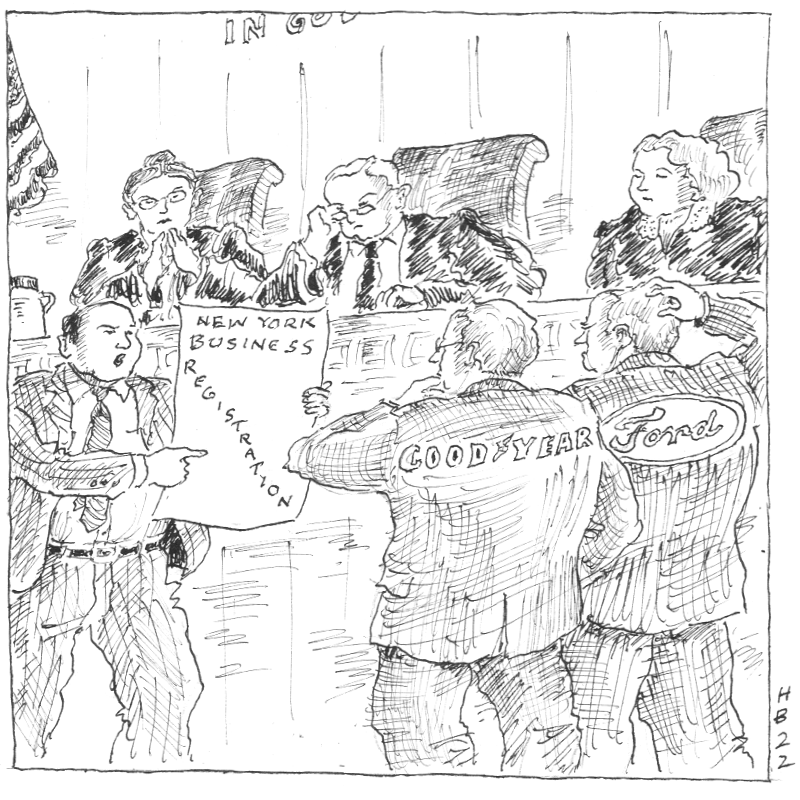

New York Court of Appeals: Foreign corporations do not submit to general personal jurisdiction in New York merely by registering to do business within the state.

Aybar v. Aybar, 37 N.Y.3d 274 (N.Y. Ct. App. 2021).

Courts in the United States distinguish between two basic forms of personal jurisdiction. General jurisdiction “permits a court to exercise jurisdiction over a defendant in connection with a suit arising from events occurring anywhere in the world,” while specific jurisdiction exists only “where the suit arises out of or relates to the defendant’s contacts with the forum state.” Over the past decade, the United States Supreme Court has substantially narrowed the scope of general jurisdiction over corporations. Where the plaintiff’s claims are unrelated to the corporate defendant’s in-state activities, a court may exercise jurisdiction over the corporation only if it is “essentially at home” there. Absent “exceptional” circumstances, this means that a corporation typically will be subject to general jurisdiction only in the state(s) where it is incorporated or maintains its principal place of business.

Courts in the United States distinguish between two basic forms of personal jurisdiction. General jurisdiction “permits a court to exercise jurisdiction over a defendant in connection with a suit arising from events occurring anywhere in the world,” while specific jurisdiction exists only “where the suit arises out of or relates to the defendant’s contacts with the forum state.” Over the past decade, the United States Supreme Court has substantially narrowed the scope of general jurisdiction over corporations. Where the plaintiff’s claims are unrelated to the corporate defendant’s in-state activities, a court may exercise jurisdiction over the corporation only if it is “essentially at home” there. Absent “exceptional” circumstances, this means that a corporation typically will be subject to general jurisdiction only in the state(s) where it is incorporated or maintains its principal place of business.

Nonetheless, courts in New York and elsewhere remain free to exercise personal jurisdiction over any foreign corporation that consents to in-state jurisdiction. But the Court of Appeals recently rejected an attempt by plaintiffs to expand general jurisdiction over foreign corporations on that basis. It held that a foreign corporation’s compliance with the statutory requirements of “registering to do business here and designating a local agent for service of process . . . does not constitute consent to general jurisdiction in New York courts.”

The plaintiffs brought suit against a car manufacturer (Ford) and tire manufacturer (Goodyear) alleging negligent manufacture and design of an automobile and tire involved in an accident. The accident occurred in Virginia, and neither the car nor the tire involved were originally sold in New York. Moreover, neither Ford nor Goodyear was incorporated or maintained its principal place of business in New York. However, both companies “were registered with the New York Secretary of State as foreign corporations authorized to do business in this state and had appointed in-state agents for service of process in accordance with the Business Corporation Law.” By taking these steps, the plaintiffs argued, Ford and Goodyear “knowingly consent[ed] to general jurisdiction in this state’s courts.”

But the Court of Appeals disagreed. It reasoned that the Business Corporation Law does not condition a foreign corporation’s “right to do business on consent to the general jurisdiction of New York courts or otherwise afford general jurisdiction to New York courts over foreign corporations that comply with [its] conditions.” The Court also rejected the plaintiffs’ suggestion that the Court’s more than century-old decision in Bagdon v. Philadelphia & Reading Coal & Iron Co., 217 N.Y. 432 (1916), stood for the proposition that “registering to do business in New York and appointing an agent for service of process constitutes consent to general jurisdiction.” Instead, the Court emphasized the earlier decision’s “narrow” focus on “the effect of service of process” as well as its “historical context,” explaining that the United States Supreme Court’s “jurisprudence defining the contours of the personal jurisdiction analysis” had since “evolved significantly.”

Two judges dissented. They stressed the “unquestioned legislative objective” behind the Business Corporation Law “to grant New York courts jurisdiction over foreign corporations.” The dissenting judges dismissed the majority’s “traipse through United States Supreme Court cases” as irrelevant because those cases had not “altered the ability to obtain jurisdiction by consent.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

Second Circuit: Federal law determines admissibility of expert opinions in diversity cases.

Sarkees v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 15 F.4th 584 (2d Cir. 2021).

In addition to deciding cases arising under federal law, U.S. federal courts also have “diversity jurisdiction” to adjudicate disputes arising under state law between citizens of different U.S. states, or between U.S. and foreign citizens. In diversity cases, state law governs all substantive issues, while procedural issues are governed by federal law. This longstanding rule is known as the “Erie doctrine.” However, determining whether an issue is substantive or procedural is not always straightforward. For evidentiary issues in particular, the Federal Rules of Evidence usually control. But “some state evidence rules might be so closely related to state substantive provisions that the state evidence rule should be applied.”

This appeal arose from a district court’s exclusion of expert evidence in a personal injury case. At issue was the opinion of the plaintiff’s expert, a physician, that the plaintiff’s repeated chemical exposure over a relatively brief period in the 1970s was a “substantial contributing factor” in his development of cancer decades later. The district court excluded the expert’s evidence as “insufficient under [New York] state tort law.” As a result, and because the plaintiff proffered no other evidence to show causation, the court granted summary judgment in favor of the defendant chemical manufacturers.

But the Second Circuit reversed. It held that federal law controls “whether an expert’s opinion is excludable” in a diversity action (just as it does in cases arising under federal law). Specifically, Federal Rule of Evidence 702 and the United States Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993), determine the admissibility of expert evidence in federal court. Rule 702 directs courts to consider the following indicia of reliability when determining the admissibility of expert evidence:

(1) whether the testimony is grounded in sufficient facts or data; (2) whether the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and (3) whether the expert has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.

In addition to these indicia, courts also consider the following factors under Daubert:

(1) whether the methodology or theory has been or can be tested; (2) whether the methodology or theory has been subjected to peer review and publication; (3) the methodology’s error rate; and (4) whether the methodology or technique has gained general acceptance in the relevant scientific community.

Applying “the standards of Rule 702 and Daubert,” the Second Circuit determined that the expert’s evidence was admissible. It found that the expert’s opinions were based on “well-respected studies” and reliable methodology. In particular, the court rejected defendants’ suggestion that the expert’s methods were not reliable because she did not conduct a “quantitative risk assessment” of the degree of exposure necessary to cause cancer. Although “precise information concerning the exposure necessary to cause specific harm” is “beneficial,” the court explained, such evidence “is not always available, or necessary, to demonstrate that a substance is toxic to humans given substantial exposure.”

The appellate court’s decision to admit the expert’s evidence effectively revived the plaintiff’s case. As the court explained: “With [the expert’s] evidence available for trial, the [defendant]’s motion for summary judgment must be denied.” But, “the weight and persuasive force” of the expert’s evidence remained for the jury to determine following an opportunity for “cross-examination and challenge by opposing evidence.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

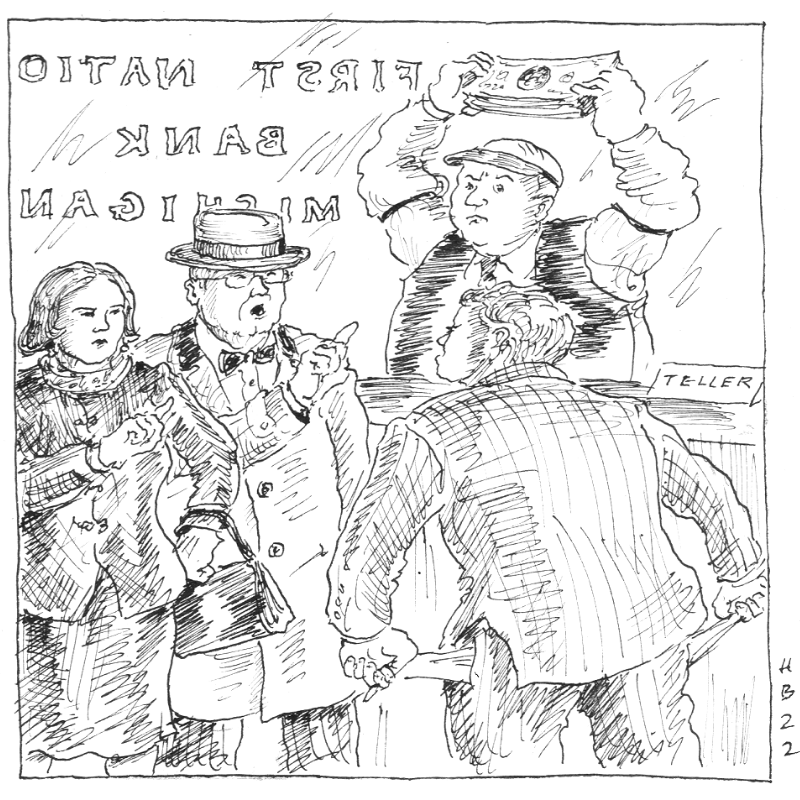

New York Court of Appeals: Judgment creditors are not liable in tort for procedural violations when they seek to enforce an otherwise valid money judgment.

Plymouth Venture Partners, II, L.P. v. GTR Source, LLC, 2021 WL 5926893 (N.Y. Dec. 16, 2021).

Article 52 of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules (CPLR) allows judgment creditors to seek the Sheriff or Marshal’s assistance in seizing assets to satisfy a money judgment. But judgment creditors must comply with the requirements of the CPLR and New York law. For example, where assets of the debtor are held by a bank or other third-party “garnishee,” the Sheriff or Marshal may levy upon the property only if the garnishee is subject to personal jurisdiction in New York. Otherwise, the judgment creditor must register the New York judgment in the state where the garnishee is located and, if necessary, obtain a court order there authorizing the seizure.

Article 52 of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules (CPLR) allows judgment creditors to seek the Sheriff or Marshal’s assistance in seizing assets to satisfy a money judgment. But judgment creditors must comply with the requirements of the CPLR and New York law. For example, where assets of the debtor are held by a bank or other third-party “garnishee,” the Sheriff or Marshal may levy upon the property only if the garnishee is subject to personal jurisdiction in New York. Otherwise, the judgment creditor must register the New York judgment in the state where the garnishee is located and, if necessary, obtain a court order there authorizing the seizure.

The Court of Appeals recently clarified what remedies are available to the debtor where a creditor ignores these requirements and seizes assets from a garnishee who is not subject to jurisdiction in New York. Following a Michigan corporation’s default under two “merchant cash advance agreements,” its lenders obtained judgments against the debtor in New York. Thereafter, a New York Sherriff and Marshal, on behalf of the lenders, successfully levied upon the debtor’s assets in a Michigan bank. The bank had no branches or other presence in New York and was not subject to jurisdiction there. But it nonetheless complied with the levy and turned over hundreds of thousands of dollars from the debtor’s Michigan bank accounts to the Sherriff and Marshal.

The debtor (now in receivership) filed separate tort actions against the lenders in federal district court seeking “to recover the amount taken from the [Michigan bank] accounts that was used to satisfy the relevant judgments,” along with unspecified consequential damages. In both cases, the district court dismissed the tort claims, reasoning that the debtor had suffered no damages because “the funds recovered by the Marshal were used to extinguish the debtor’s valid debt owed under a valid court judgment.” The cases were later consolidated on appeal, and the Second Circuit certified two questions to the Court of Appeals: (1) whether “a judgment debtor suffers cognizable damages in tort” where its property is seized to satisfy a valid money judgment but the levy fails to “comply with the [CPLR’s] procedural requirements”; and (2) if so, whether the debtor must first seek relief under the CPLR before it may “bring a tort claim against either the judgment creditor or the marshal.”

In a sweeping 4-3 decision, the Court of Appeals ruled that a motion for relief under article 52 of the CPLR is the debtor’s exclusive remedy against a creditor’s procedurally improper efforts to collect on an otherwise valid judgment. On that basis, the four-judge majority found it unnecessary to address either certified question as formulated. As they explained, article 52 specifically empowers New York courts “at any time [to] make an order denying, limiting, conditioning, regulating, extending or modifying the use of any enforcement procedure.” By codifying this remedy in article 52, the “legislature ‘provided the avenues for relief it deemed warranted.’” The majority rejected as “not workable” any attempt to “recast” “allegations of non-compliance with article 52 in the course of enforcing valid judgments . . . into common law tort claims.”

Three judges dissented. Two of the dissenting judges would have held that a judgment debtor lacks a viable tort claim “when the damages sought are limited solely to the value of the seized property.” They would have found it unnecessary to reach the second certified question, but nonetheless criticized as without “legal basis” the majority’s conclusion “that the failure to seek relief under CPLR article 52 precludes a tort action.” Writing separately, a third judge similarly emphasized that nothing about article 52’s “statutory processes for obtaining, enforcing, and challenging [money] judgments . . . supplants or limits” a debtor’s ability to assert “a common law tort claim against an allegedly improper judgment execution.” But that judge additionally would have deemed it possible that “an accelerated and procedurally improper [judgment enforcement] process could proximately cause consequential damages.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.