Second Circuit: Original owner’s claim for recovery of million-dollar painting from good faith purchaser held timely under New York law.

Abbott Laboratories v. Feinberg, 2023 WL 19076 (2d Cir. Jan. 3, 2023).

Replevin is a cause of action for the return of property wrongfully taken or held. In New York, as long as a stolen object remains in the thief’s possession, the three-year statute of limitations for replevin runs from the time of the theft. But, where the property is in the hands of a good-faith purchaser, the claim does not accrue until the true owner demands the object’s return and the purchaser refuses to give it back. As a result, in New York, unlike many other jurisdictions, the true owner may have a timely claim for replevin against the good-faith purchaser years or even decades after the theft.

Replevin is a cause of action for the return of property wrongfully taken or held. In New York, as long as a stolen object remains in the thief’s possession, the three-year statute of limitations for replevin runs from the time of the theft. But, where the property is in the hands of a good-faith purchaser, the claim does not accrue until the true owner demands the object’s return and the purchaser refuses to give it back. As a result, in New York, unlike many other jurisdictions, the true owner may have a timely claim for replevin against the good-faith purchaser years or even decades after the theft.

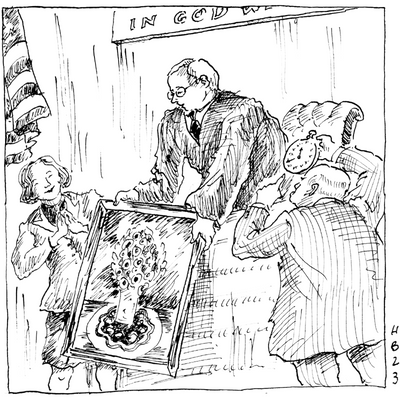

Applying this rule, the Second Circuit affirmed the trial court’s judgment granting Abbott Laboratories’ claim for return of the painting Maine Flowers by the American Modernist painter, Marsden Hartley. In 1987, Abbott delivered Maine Flowers to Robert Duncan for restoration. Rather than restoring the painting and returning it, however, Duncan created a forged copy, which he gave to Abbott while selling off the original. After a series of transactions, the genuine original ended up in the possession of Carol Feinberg, who acquired it in 1993. Abbott did not discover the theft until 2016, and by 2018, it successfully traced the artwork to Feinberg.

After Feinberg refused Abbott’s demand to return the painting, the parties filed competing lawsuits in the Northern District of Illinois (Feinberg) and the Southern District of New York (Abbott). Ultimately, both cases were consolidated in the Southern District of New York. And, after a bench trial, the district court there entered judgment granting Abbott’s claim for recovery of the painting.

On appeal, Feinberg’s principal argument for reversal was that the lower court should have applied Illinois’ statute of limitations, under which Abbott’s claim were time-barred. But the Second Circuit disagreed. In a summary order, it held that New York law applied because Feinberg’s refusal to hand over the painting took place in New York, where the painting was located. On that basis, Abbott’s claim was timely because it did not accrue until 2018.

The Second Circuit also rejected Feinberg’s other arguments. First, Feinberg maintained, she acquired good title to the painting under a statutory exception to the usual New York rule that a thief cannot convey title to stolen property. Under New York’s Uniform Commercial Code, Feinberg argued, Duncan was able to convey Abbott’s title to subsequent purchasers because he was a merchant who regularly dealt in goods of this kind, and Abbott had “entrusted” the painting to him. But the court disagreed, finding no evidence that Duncan was in the business of selling (as opposed to restoring) paintings.

Finally, the court rejected Feinberg’s laches defense. Specifically, Feinberg argued that Abbott’s delay in bringing the case prevented her from establishing her “entrustment” defense because Duncan and other relevant witnesses were now deceased, so that she could no longer obtain their testimony as to the nature of Duncan’s business. But the Second Circuit, applying a deferential “abuse of discretion” standard, accepted the district court’s conclusion that Abbott’s delay in discovering the theft was reasonable because Duncan had returned the forgery to Abbott in its original frame and with the original labels, and because Abbott, at the time, was preoccupied with authenticating other, more valuable works in its collection.

Read the court’s full decision here.

Southern District of New York: Chinese data privacy law did not absolve cryptocurrency firm from compliance with its U.S. discovery obligations.

Owen Elastos Foundation, 2023 WL 194607 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 11, 2023).

As a rule, foreign data privacy laws and other blocking statutes do not “deprive an American court of the power to order a party subject to its jurisdiction to produce evidence even though the act of production may violate” foreign law. Instead, federal courts conduct a two-step analysis when faced with a party’s claim that compliance with its U.S. discovery obligations will require it to violate foreign law. First, the party resisting discovery must persuade the court that “the discovery sought is indeed prohibited by foreign law.” If the court finds that it is, the court will then undertake a “comity analysis” to “determine the weight to be given to the foreign jurisdiction’s law.”

Courts in the Second Circuit consider seven factors when deciding whether comity calls for deference to the foreign blocking statute in a particular case:

(1) the importance to litigation of the documents or other information requested;

(2) the degree of specificity of the request;

(3) whether the information originated in the United States;

(4) the availability of alternative means of securing the information; and

(5) the extent to which noncompliance with the request would undermine important interests of the United States, or compliance with the request would undermine the important interests of the state where the information is located; and

(6) the hardship of compliance on the party or witness from whom discovery is sought; and

(7) the good faith of the party resisting discovery.

Defendant Elastos Foundation, registered in Singapore and with offices in Shanghai and Beijing, was in the business of creating and selling cryptocurrency tokens. Plaintiffs were a putative class claiming that the tokens were securities that Elastos was required, but failed, to register with the U.S. SEC. At the start of discovery, Elastos explained that its employees used their personal devices for both Elastos and non-Elastos communications, and that the data at issue were stored both on Elastos servers in China and on Google servers in the United States.

When plaintiffs sought documents from nineteen individuals, including both U.S.- and China-based custodians, Elastos resisted, arguing that the Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (the “PIPL”) required consent of the China-based custodians before producing, or even collecting, their documents, and that several custodians did not consent.

But the court rejected that argument. Joining another court in the Northern District of California, it concluded that the PIPL does not prohibit processing personal information for the purpose of U.S. litigation. Rather, under two enumerated statutory exceptions, personal information processing is permissible if “the processing is necessary for the performance of statutory duties or obligations,” or under “other circumstances provided by laws or administrative regulations.” Compliance with U.S. discovery obligations, the court held, fell within those exceptions. The court also found that Chinese law did not reach the data stored on Google servers in the U.S.

Moreover, even assuming that the PIPL prohibited the disclosure, the court found that the first, fourth, fifth, and sixth factors of the comity analysis weighed in favor of production. Critically, it explained, the “most important” fifth factor, which weighs the relevant interests of the United States and China, “weigh[ed] decidedly in favor of production.” The U.S. had both an “obvious interest” in applying its discovery rules in U.S. litigation and a “significant interest” in protecting investors under its securities laws. On the other hand, China’s interests were relatively weak, given that Elastos was merely a Singaporean entity that happened to store data on Chinese servers.

Read the court’s full decision here.

First Department: Judges split on whether garbled contract language was open to “multiple reasonable interpretations” or the product of “obviously inadvertent errors”.

MAK Tech. Holdings Inc. v. Anyvision Interactive Techs. Ltd., 181 N.Y.S.3d 219 (N.Y. App. Div. 2022).

Under New York law, “a written agreement that is clear, complete and subject to only one reasonable interpretation must be enforced according to the plain meaning of the language chosen by the contracting parties.” On the other hand, a contract is ambiguous if it is “susceptible of multiple reasonable interpretations.” Ambiguous contracts require consideration of extrinsic evidence (including documents and witness testimony) to establish the parties’ intent.

Under New York law, “a written agreement that is clear, complete and subject to only one reasonable interpretation must be enforced according to the plain meaning of the language chosen by the contracting parties.” On the other hand, a contract is ambiguous if it is “susceptible of multiple reasonable interpretations.” Ambiguous contracts require consideration of extrinsic evidence (including documents and witness testimony) to establish the parties’ intent.

Plaintiff MAK Technology entered into a Referral Agreement with defendant Anyvision, a developer of AI-driven facial recognition software. The Agreement provided that MAK would refer businesses to Anyvision, in exchange for a fee, for a “Term” of three years from the Agreement’s November 23, 2017 “Execution Date.” Later, in 2018, the parties entered into two amendments to the Agreement. Finally, in July 2021, after the Agreement’s three-year Term had expired, Anyvision announced it had raised $25 million from a company referred by MAK. When Anyvision refused to pay the resulting referral fee, MAK sued for breach. Anyvision, in turn, moved to dismiss.

The survival of MAK’s claim hinged on whether one of the amendments to the Agreement at least potentially could be read as having postponed the operative Execution Date by nine months from November 23, 2017, when the Agreement was signed, until August 24, 2018, when the amendment was executed. If that was the parties’ intent, the Agreement’s Term likewise would have been extended by nine months. However, the critical language in the amendment was garbled. It read:

Each of the undersigned hereby agrees that the with affect as of the date hereof and notwithstanding anything to the contrary in the Agreement, the Agreement shall be amended as follows . . .

Stretching to interpret the quoted language, a three-judge majority ruled that it was susceptible to “multiple reasonable interpretations” and therefore ambiguous. According to the majority, the bolded words could mean either “with effect as of the date hereof” or “with the Effective Date as the date hereof.” Because the provision was “literally unclear and ambiguous,” the majority concluded, it “must be interpreted in light of extrinsic evidence.” On that basis, the court affirmed the trial judge’s denial of Anyvision’s motion to dismiss, in effect allowing the case to proceed.

The two dissenting judges, understandably, were “unable to see the ambiguity the majority claim[ed] to detect.” According to the dissent, the absence of any language in the amendment “purporting to change the definition of the term ‘Effective Date’ in the original Agreement” confirmed that the “obviously inadvertent errors” in the operative clause could not “reasonably be construed to change the . . . Agreement’s definition of ‘Effective Date.’”

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.