Practical Considerations for Holding a Remote Arbitration Hearing

June 2020 – James Hosking and Marcel Engholm Cardoso recently wrote an article about things to consider when participating in virtual arbitration hearings. Publication of the article is forthcoming in the New York Dispute Resolution Lawyer, Summer 2020, Vol. 13 No 2, a publication of the New York State Bar Association Dispute Resolution Section. The full article is available below.

It is not uncommon for portions of arbitrations to be held “remotely,” i.e. without all participants being in the same room. For years, procedural conferences, oral arguments and some witness testimony have been conducted using telephones and video platforms. But it has taken the COVID-19 pandemic to cause us to hold entire hearings remotely and, given social distancing restrictions, to do so where all participants (arbitrators, counsel, witnesses, court reporters, etc) are attending remotely. Necessity is the mother of invention.

Although not always known for being enthusiastic about change, this is one innovation lawyers should embrace. There are undoubtedly benefits to remote hearings: reduced travel (with its cost, jetlag and environmental impact); potentially fewer calendar restrictions; and ideally more streamlined arguments. After all, our clients have been negotiating and closing complex deals remotely for years. But not all cases are suited to being held remotely. Arbitrators should carefully consider whether a remote hearing is appropriate and, if so, devise the best procedure to ensure it runs smoothly and fairly.

This article suggests some practical aspects of conducting a remote hearing—whether as arbitrator or counsel—that should guide one in deciding whether, and how, to proceed remotely. But the note is not intended to be prescriptive. Importantly, remote hearings offer a fresh opportunity to all participants to re-think what procedures may best meet the specific needs of the case.

I. Technological Considerations

The two most fundamental issues are the technological set-up and the choice of video platform.

(a) The Technological Set-Up

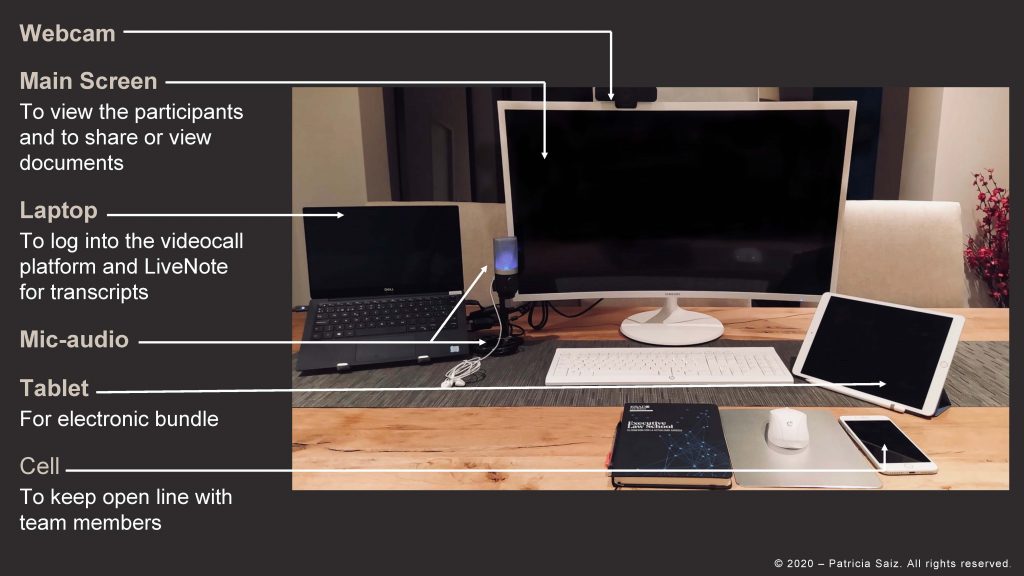

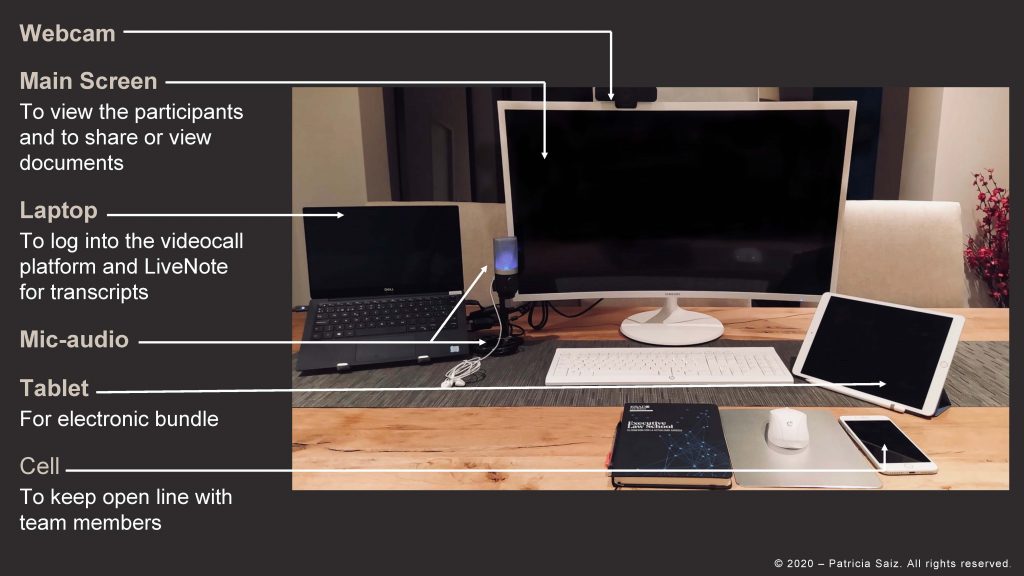

Whether as counsel or arbitrator, the practitioner should have enough devices to (a) see all participants; (b) hear the participants and any required interpretation; (c) see documents the parties project on-screen, as well as access soft copies of the record; (d) have a live-transcript feed; and (e) have an open line of communication with immediate colleagues. All of this could be accomplished with a single laptop. However, some additional equipment can vastly improve the experience.

The preferred set-up would have a separate screen or device for each of the aforementioned components, as seen in the following photograph.[1]

Thus, in addition to a laptop screen, consider using an external larger screen or smart TV to see video feeds, a tablet to access documents or see the live-transcript, and a phone with a text message or WhatsApp group. Video quality can be improved by using a computer with a powerful graphics card, as well as an external HD camera. Using a headset improves audio quality and can be particularly helpful when separate audio channels are used for the witness and live interpretation. The headset may have a built-in microphone or, if possible, use an external remote microphone—do not rely on a laptop. Finally, a continuous and fast internet connection is essential. Rather than connecting to a wi-fi network, if possible, use a direct ethernet connection.

(b) The Platform

There are multiple products providing video-conference services, such as BlueJeans, Cisco WebEx, Microsoft Teams and Zoom. Consider whether the platform addresses the needs of the particular case, which may include (a) whether it supports the required number of attendees; (b) does it allow an additional channel for interpretation; (c) whether it allows for parallel break-out rooms; (d) and if it permits live presentation of documents, among others. Check carefully the security protocols available, bearing in mind that some countries, institutions or companies may have specific security needs. For institutional arbitrations, a decisive factor may be which platform the institution is familiar with and whether a tribunal secretary or case manager will be able to assist with logistics. In this respect, there is a wealth of knowledge amongst institution staff who have seen what works and what does not.

Importantly, access to the platform should be obtained early to allow everyone to get familiar with its operation. Whether arbitrator, counsel or witness, conduct a mock hearing to ensure you are fully prepared. Do so with enough advance time to remedy any problems.

II. Considerations for Arbitrators

Technological challenges make early planning even more important than in an in-person hearing. A comprehensive protocol, whether agreed or ordered by the tribunal, is essential to ensuring the hearing runs smoothly. Consider addressing the following.

-

- Parties’ agreement to a remote hearing. If not agreed, have a well-reasoned order as to why the arbitration is proceeding with a remote hearing. If possible, include an explicit waiver of any challenge to the award based on the hearing being conducted remotely.

- Hearing times. Hearing days may need to be shorter or have unusual start/finish times to accommodate different time-zones. Consider having more frequent short breaks to allow participants to re-focus and address any technological issues.

- Host. Establish the host’s level of control (e.g., mute microphones, switch cameras on and off, and control who joins the room). Establish whether this role will be exercised by the institution, a tribunal secretary, the chair, IT staff, or a combination of them.

- Privacy and security. At a minimum, the hearing room must be password protected. The parties should disclose a participant list in advance and the host should ensure there are no unauthorized attendees. Consider other security issues like two-factor authentication, is a video/audio recording being made and separate passwords for virtual break-out rooms. Entering into a cyber-security protocol is even more important than usual.

- Contingency measures in case of sudden technical failures. Consider a protocol whereby in the event of a problem, microphones and cameras are turned off to avoid concerns with ex parte Key participants may be required to have backup devices. Arbitrators should have alternative communication channels if necessary to confer.

- Video directives. Determine if all participants should have their cameras on at all times. It may be preferable to limit the screen to only the Tribunal, the witness and the examining lawyer, especially with a large number of participants. Some platforms may also offer more advanced split-screen technology or use of a non-static camera, but remember that simpler may be better.

- Audio directives. Agree to have all participants muted except for the immediate speaker (and any interpreter) to avoid background noise. As to interpreters, this may be as simple as opening a separate audio-only meeting. But more sophisticated platforms may offer a separate audio channel in the same meeting. The court reporter may also need an open line to raise any problems immediately.

- Documents. Determine how document bundles will be shared (hard copies, FTP or Virtual Data Room); if possible, use an agreed joint bundle and/or key-documents to avoid switching folders or systems. When using electronic copies, determine if references will be made to the .pdf/.doc page or to a page number embedded in the document. Consider providing in advance a hard copy cross-examination bundle, rather than screen sharing, to avoid unnecessary delays and save screen real estate. If so, agree on a protocol for delivery, whether electronically or in hard copies, and have the witness undertake not to access the bundle before testifying.

- Examination of witnesses. The twin objectives are to ensure the best audio/video quality while protecting due process. If witnesses are able to leave home, consider having testimony from a neutral location with good IT (e.g. a law firm or hearing center). Give directives to ensure there is no one else in the room to coach the witness (e.g., use a 360-degree camera or ask the witness to show the room). Alternatively, consider whether it may be more efficient to have a party representative present (abiding by social distancing directives) to assist with logistical issues. Technology and time zone constraints may mean that witness evidence needs to be staggered.

- Objections. Competing voices will make the hearing incomprehensible. Establish a protocol for making objections (to the extent they are necessary). This could be as simple as unmuting and turning video on, or using the “raise hand” functionality. Consider allowing the host to mute the witness once an objection is raised.

- Narrower scope. A remote hearing is most efficient when it can focus on the evidence and issues that cannot be dealt with exclusively through written submissions and documents. Consider procedural tools like an agreed list of issues, agreed facts or bifurcation of stand-alone issues to narrow the remote hearing to focused evidentiary issues.

In addition to these issues that may appear in a procedural order, consider how the arbitrators will attend the remote hearing and how deliberations will be conducted. The arbitrators might be able to sit “together” in the same location with social distancing precautions. If not, schedule regular breaks with a secure audio/video line to be able to discussing issues timely. In addition, many arbitrators use email, messaging or WhatsApp to allow real-time comments on pressing issues.

III. Considerations for Counsel

Remote hearings should not just duplicate an in-person hearing. Consider some of the following unique challenges, opportunities and strategies.

-

- Written submissions are even more important than usual. Watching the hearing through a screen is less dynamic than being present in an actual hearing room. As a result, it may be more difficult to assess whether the tribunal is following along. Submission of written pre-hearing briefs or focused openings may be useful. Perhaps it is possible to have, for example, an “afternoon off” between openings and witness testimony to allow the tribunal to focus. Post-hearing briefs and directed questions from the tribunal may be all the more important.

- Witness preparation. Obviously, it is incumbent on producing counsel to ensure the witness is familiar with the video platform, with using electronic bundles, and has a secure internet connection. For a technologically insecure witness, consider agreeing to having someone (perhaps a third party paralegal) available to assist. At the same time, make sure the witness is not lulled into being too relaxed by the less formal setting of a remote hearing.

- Pace and scope of cross-examination and redirect. Cross-examinations are, arguably, less effective due to video lag and the fact that there is less immediacy. Counsel should be less expansive and more surgical in planning their cross-examination. Consider also how the witness will interact with exhibits, which almost certainly is more time-consuming. Accordingly, use exhibits sparingly. For redirect, counsel may have to react quickly to “share” an exhibit or a screen-shot of the transcript.

- Use of exhibits. In general, less is more. Consider constructing a cross-examination that is less dependent on documentary exhibits, e.g. focused more on statements. To avoid the potential for time delays and errors in loading a document from a joint bundle folder, consider using a set electronic cross-bundle or, even better, a hard copy bundle sent in advance.

- Advocacy style. Given possible audio constraints, the live transcript may be even more important than in an in-person hearing. To this end, be extra careful about moderating speed of presentation and consider using clear verbal “signposts” so that the tribunal can follow along in real-time and in using the transcript in deliberations. Counsel should also consider that the camera frame will have the tribunal focus exclusively on the speaker’s face, affecting the perception of non-verbal cues. While it is unclear whether this aids or hinders the viewer’s focus, counsel must be mindful of this particularity and consider adjusting delivery style.

- Team communication. Hurriedly scribbled Post Its are a thing of the past. Have an open line of communication, such as a permanently open break room, email feed or WhatsApp group. It may be best to have a designated colleague reviewing the feed and filtering comments to the first chair. More generally, and more so than usual, counsel may need to assign specific roles to team-members to better manage the several moving parts of the remote hearing.

IV. What other resources are available to help?

As initial fears about remote hearings have faded, their use has become almost common place. Of course, the real test will arrive once the public health emergency abates and in-person hearings become a more viable option—the authors are confident that remote hearings (especially when not constrained by social distancing) will remain an important part of the arbitration scene. In the meantime, there are a number of excellent practical resources available to aid arbitrators and counsel (many of which are collated on the NYIAC website).[2] These include:

-

- Guidance Notes:

- AAA-ICDR Virtual Hearing Guide for Arbitrators and Parties[3]

- CIArb Guidance Note on Remote Dispute Resolution Proceedings[4]

- Delos Checklist on holding Arbitration and Mediation Hearings in Times of COVID-19[5]

- Hague Conference Draft Guide to Good Practice on the Use of Video Links[6]

- ICC Guidance Note on Possible Measures Aimed at Mitigating the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic[7]

- ICCA-NYC Bar-CPR Protocol on Cybersecurity in International Arbitration[8]

- Joint Statement on Arbitration and COVID-19[9]

- Seoul Protocol on Video Conferencing in International Arbitration[10]

- Model Procedural Orders:

- AAA-ICDR Model Order and Procedures for a Virtual Hearing via Videoconference[11]

- CPR’s Annotated Model Procedural Order for Remote Video Arbitration Proceedings[12]

Publication forthcoming in the New York Dispute Resolution Lawyer, Summer 2020, Vol. 13 No. 2, a publication of the New York State Bar Association Dispute Resolution Section.

[1] Image used with the kind permission of Patricia Saiz González. Email: patricia.saiz@esade.edu

[2] https://nyiac.org/resources/covid-19-resources/.

[3] https://go.adr.org/rs/294-SFS-516/images/AAA269_AAA%20Virtual%20Hearing%20Guide%20for%20Arbitrators%20and%20Parties%20Utilizing%20Zoom.pdf.

[4] https://www.ciarb.org/media/8967/remote-hearings-guidance-note.pdf.

[5] https://delosdr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Delos-checklist-on-holding-hearings-in-times-of-COVID-19-v2-as-of-20-March-2020.pdf.

[6] https://assets.hcch.net/docs/e0bee1ac-7aab-4277-ad03-343a7a23b4d7.pdf.

[7] https://iccwbo.org/publication/icc-guidance-note-on-possible-measures-aimed-at-mitigating-the-effects-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

[8] https://www.arbitration-icca.org/publications/ICCA_Report_N6.html.

[9] https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2020/04/covid19-joint-statement.pdf.

[10] https://globalarbitrationreview.com/digital_assets/9eb818a3-7fff-4faa-aad3-3e4799a39291/Seoul-Protocol-on-Video-Conference-in-International-Arbitration-(1).pdf.

[11] https://go.adr.org/rs/294-SFS-516/images/AAA270_AAA-ICDR%20Model%20Order%20and%20Procedures%20for%20a%20Virtual%20Hearing%20via%20Videoconference.pdf.

[12] https://www.cpradr.org/resource-center/protocols-guidelines/model-procedure-order-remote-video-arbitration-proceedings.

Click here to view our full list of COVID-19 Information and Resources.