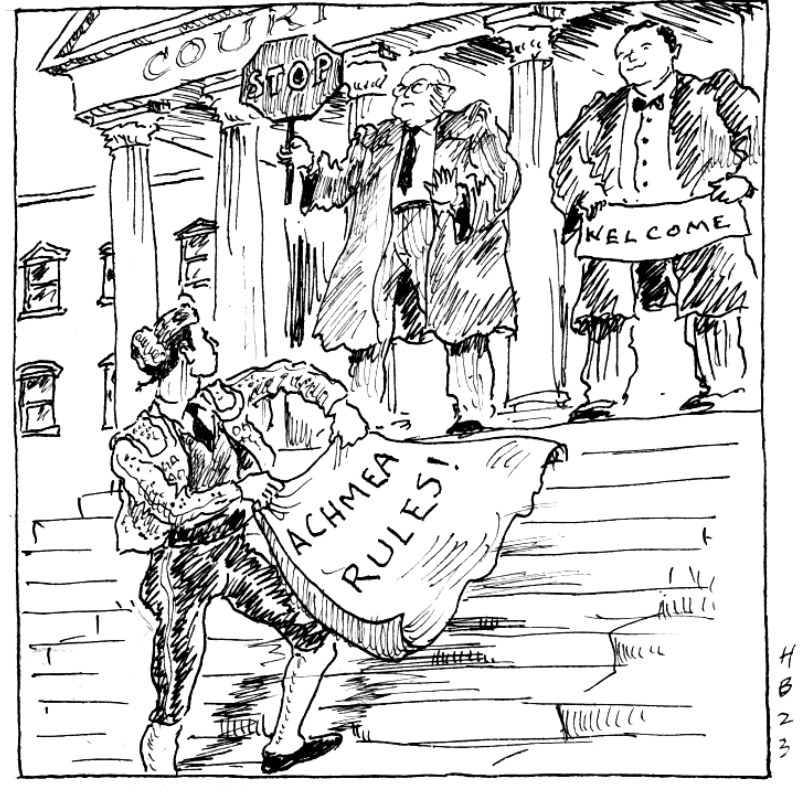

DC district court reaches conflicting decisions whether EU high court’s landmark decision deprives US courts of jurisdiction to enforce investors’ arbitral awards against Spain.

9REN Holding SARL v. Kingdom of Spain, No. 1:19-cv-1871-TSC (D.D.C. Feb. 15, 2023); Blasket Renewable Investments LLC v. Kingdom of Spain, No. 21-3249 (RJL) (D.D.C. March 31, 2023).

The Slovak Republic v. Achmea B.V., the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) held that arbitration agreements in European Union Member States’ bilateral investment treaties violate EU law if they vest arbitrators with the authority to decide questions of EU law without review by EU courts. In Republic of Moldova v. Komstoy, the CJEU held that its decision in Achmea extends to arbitration agreements in multilateral treaties between EU Member States, such as the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), a multilateral agreement intended to promote cooperation and investment in the energy sector.

The Slovak Republic v. Achmea B.V., the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) held that arbitration agreements in European Union Member States’ bilateral investment treaties violate EU law if they vest arbitrators with the authority to decide questions of EU law without review by EU courts. In Republic of Moldova v. Komstoy, the CJEU held that its decision in Achmea extends to arbitration agreements in multilateral treaties between EU Member States, such as the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), a multilateral agreement intended to promote cooperation and investment in the energy sector.

In the wake of Achmea and Komstoy, US courts deciding petitions to recognize arbitral awards against European Union Member States have grappled with the jurisdictional implications of these decisions. US courts have jurisdiction over such cases exclusively to the extent permitted by the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). The FSIA provides that foreign states are presumptively immune from suit in the US, and US courts therefore lack subject matter jurisdiction over such actions, unless one of the FSIA’s enumerated exceptions to immunity apply. One such exception is the “arbitration” exception (FSIA § 1605(a)(6)), which provides that a foreign state is not immune against suits to enforce arbitration awards if the foreign state agreed to arbitrate and is also a signatory to any treaty or international agreement, such as the New York Convention, calling for the enforcement of such awards in the US.

In two recent decisions – 9REN Holding SARL v. Kingdom of Spain and Blasket Renewable Investments v. Kingdom of Spain – the United States District Court for the District of Columbia addressed whether Achmea and Komstoy deprived the court of jurisdiction under the FSIA’s arbitration exception to confirm awards against Spain. Although both cases presented analogous facts and the same jurisdictional question, the courts reached opposite conclusions.

First, the similarities. 9REN and Blasket each concerned arbitration awards against Spain in favor of investors from other EU Member States who had invested in Spanish renewable energy projects. The investor in 9REN was a Luxembourg corporation, who had invested in seven Spanish solar power projects in reliance on certain Spanish legislation incentivizing such investments, which Spain later rolled back. The investors in Blasket were Dutch companies who had invested in Spanish renewable energy projects in reliance on certain tax incentives, which Spain later rescinded. The investors in both cases claimed that Spain’s rescission of the favorable legislation violated the investors’ rights under the ECT. In accordance with the ECT’s arbitration provision, the investors in both commenced arbitration against Spain. While 9Ren pursued arbitration under the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (ICSID Convention), the investors in Blasket initiated ad hoc arbitration in Geneva under the UNCITRAL Rules. In both cases, the tribunals issued substantial damages awards against Spain.

In each case, Spain unsuccessfully challenged the award on jurisdictional grounds. In 9REN, an ICSID Annulment Committee denied Spain’s jurisdictional challenge. In Blasket, after the arbitrators rejected Spain’s challenge, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court refused to annul the award. The investors in both cases filed petitions in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, the default venue for suits against foreign sovereigns, seeking confirmation of their respective awards.

Spain argued in both cases that the court lacked subject-matter jurisdiction under the FSIA. Relying on Achmea and Komstoy, Spain argued that it never had the authority or legal capacity to agree to the ECT’s arbitration provisions, and thus there was no agreement on Spain’s part to arbitrate. That is where the similarities end. The 9REN court held it had jurisdiction over the enforcement petition, while the Blasket court held that it lacked jurisdiction.

9Ren was decided first. The court explained that jurisdiction under the FSIA’s arbitration exception is predicated on a narrow set of jurisdictional facts, namely “the existence of an arbitration agreement, an arbitration award and a treaty governing the award.” On the other hand, a challenge to the “arbitrability of a dispute is not a jurisdictional question under the FSIA,” but rather goes to the merits of the petition.

Applying this framework, the 9REN court held that Spain’s claim that it lacked the legal capacity to agree to the ECT’s arbitration provision went to the arbitrability of the investor’s claims, not the existence of the arbitration agreement. According to the court, “[t]he assertion that a party lacked a legal basis to enter or invoke an arbitration agreement is not a challenge to the jurisdictional fact of that agreement’s existence.” Rather, Spain’s assertion “goes to arbitrability even if it contends that the ECT was not validly applied.” Thus, the court held, an award debtor may “assert the lack of a legal basis for entering an agreement to contest an award’s merits…, but not to rebut a plaintiff’s evidence that an agreement to arbitrate exists.” The court noted that “there is no question as to the existence of the ‘copies of [the underlying treaty], the notice of arbitration, and the tribunal’s decision.” It therefore concluded that whether Spain “lacked a legal basis” to enter the arbitration agreement went to the merits of the petition, and Spain could not deploy this “arbitrability” argument as a “backdoor challenge to FSIA jurisdiction.”

After finding jurisdiction, the court moved to considering 9REN’s motion for a preliminary anti-suit injunction enjoining Spain from continuing to prosecute an action in Luxembourg, which sought to enjoin 9REN from continuing to prosecute its petition to confirm the award before the DC court. The court found that the anti-suit injunction, while an extraordinary measure, was warranted to preserve its own jurisdiction, as Spain’s “express and primary purpose” in pursuing the Luxembourg action was to terminate the proceeding before the DC court.

9Ren also had to demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits of its petition to confirm the award to obtain a preliminary injunction. In that context, the court ruled that “9Ren’s success in confirming the award highly likely” because “the court’s role in enforcing an ICSID arbitral award is … exceptionally limited.” Once the court is satisfied that it has jurisdiction, it must accord ICSID awards the same full faith and credit as the judgment of any US state. Thus, the court had no basis to scrutinize the substance of the award, including the finding that the arbitrators had jurisdiction, notwithstanding Achmea and Komstroy. Spain has appealed the court’s decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Blasket was subsequently decided by a different judge on the same DC court. The court applied the same basic jurisdictional framework, but expressly rejected the 9REN court’s distinction between the arbitrability and the jurisdictional analyses. The court found that it lacked jurisdiction to enforce the award at issue because Achmea and Komstroy rendered Spain’s agreement to arbitrate in the ECT a nullity. For the Blasket court, the issue was not merely whether the investors’ claims fell within the scope of a valid arbitration agreement, but rather, whether any arbitration agreement existed at all. Because the court read Achmea and Komstroy to hold that EU Member States such as Spain lacked legal capacity to agree to arbitrate, “no valid agreement to arbitrate existed.” Finding that petitioners failed to establish the jurisdictional predicate of a valid arbitration agreement, the Blasket court held the FSIA’s arbitration exception did not apply, and it therefore lacked jurisdiction to hear the petition.

In reaching this conclusion, the Blasket court also rejected investors’ arguments that it should defer to the arbitrators’ prior determination that a valid arbitration agreement existed. For the court, the question was whether, “under the law applicable to them, the parties were incapable of entering into an agreement to arbitrate anything at all.” This, the court reasoned, could not be a question for the arbitrators, because “deference to the tribunal in such a case effectively assumes away the antecedent question of whether the parties could have agreed to [delegate that question to the arbitrators] in the first instance.” Blasket too is now on appeal to the DC Circuit.

The DC Circuit will hear these appeals in these cases together, and will hopefully provide some much needed clarity on the impact of Achmea and Komstoy on the jurisdiction of US courts to entertain petitions to confirm awards in favor of European investors against EU Member States.

Read the court’s full decision here.

Court joins majority of federal appellate circuits in recognizing that the New York Convention permits countries to apply their own domestic laws to annul awards issued under that country’s law.

Corporación AIC SA v. Hidroeléctrica Santa Rita SA, 66 F.4th 876 (11th Cir. 2023).

The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards (New York Convention) is codified in Chapter 2 of the FAA (9 U.S.C. § 201 et seq). It governs not only awards issued outside of the US, but also “non-domestic” awards governed by the Convention – those awards issued by tribunals seated in the US, which involve one or more foreign parties or have some other reasonable relation with one or more foreign states. The Second, Third, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Ninth, Tenth and D.C. Circuits have all held that, in addition to the grounds for refusing to recognize and enforce awards found in Article V of the Convention, FAA Chapter’s 1’s vacatur standards (FAA, § 10) also apply to non-domestic awards and govern their validity.

The Eleventh Circuit, whose jurisdiction includes appeal from district courts in Miami, had been an outlier, having previously held that Article V of the Convention provided the exclusive grounds on which a court may not only refuse to recognize or enforce an award governed by the Convention, but also vacate awards seated in the U.S. In Corporación AIC, the Eleventh Circuit revisited this issue, overruled its prior decisions, and held that the grounds for vacatur in FAA § 10 do apply to nondomestic awards governed by the Convention.

Other federal appeals courts had reasoned that Article V(1)(e) of the Convention – permitting an enforcing court to refuse enforcement of an award that “has been set aside or suspended by a competent authority of the country in which … [it] was made” – necessarily contemplates that the courts at the seat may apply their own domestic arbitration laws to vacate a Convention award. Agreeing with its sister circuits, the Eleventh Circuit acknowledged that its prior decisions erroneously “equated the defenses to recognition and enforcement [in Article V] with the grounds for vacatur.” The court held its prior decisions were wrong because Article V refers to grounds for refusing “[r]ecognition and enforcement,” which “serve different purposes and request different relief than vacatur.” “Recognition and enforcement seek to give effect to an arbitral award, while vacatur challenges the validity of the award and seeks to have it declared null and void.” The reference in Article V(1)(e) to “set aside or suspension” referred to what the FAA terms “vacatur,” i.e., invalidation or annulment of an award. Article V(1)(e) therefore distinguishes between the legal seat of the arbitration (i.e., the “primary jurisdiction”) and other signatory jurisdictions in which the award may be recognized (i.e., “secondary jurisdictions”). Under the Convention, “only a court in the primary jurisdiction can vacate an arbitral award,” which then becomes a ground on which a secondary jurisdiction may refuse recognition and enforcement.

The Convention, however, “does not purport to regulate the procedures or set out the grounds for vacatur in the primary jurisdiction.” Rather, “the Convention requires courts to rely on domestic law to fill gaps.” Thus, the court held, “in a case under the Convention where the United States is the primary jurisdiction—the jurisdiction where the arbitration was seated or whose law governed the conduct of the arbitration—the grounds for vacatur of an arbitral award are set out in domestic law, currently Chapter 1 of the FAA.”

Following Corporación AIC, every federal appellate circuit to have addressed the issue is now in agreement that the grounds for vacatur in FAA § 10 apply to nondomestic awards.

Read the court’s full decision here.

Bolivian annulment order not entitled to comity when award debtor sought and obtained annulment after the US district court entered judgment recognizing the award.

Compañía de Inversiones Mercantiles S.A. v. Grupo Cementos de Chihuahua S.A.B. de C.V., 58 F.4th 429 (10th Cir. 2023).

Article V of the New York Convention (codified in Chapter 2 of the Federal Arbitration Act) sets forth the exclusive grounds on which US courts may refuse to recognize and enforce arbitration awards governed by the Convention and issued under the laws of a foreign state. Article V(1)(e) provides that “recognition and enforcement of the award may be refused” if “the award … has been set aside or suspended by a competent authority of the country in which, or under the law of which, that award was made.” This permits a US court to deny enforcement of an award that has been vacated or annulled by a court at the seat. While the Convention does not mandate non-recognition of such awards, under principles of international comity, US courts will ordinarily give effect to foreign annulment orders and refuse enforcement of the annulled award. It is only in the rare and narrow circumstances in which refusing enforcement violates a strong US public policy that US courts will enforce an award that has been set aside at the seat.

In Compañía de Inversiones Mercantiles, the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit held that such extraordinary circumstances existed to justify enforcing the underlying award, notwithstanding that it had been annulled by a Bolivian court. Until Compania, the Second Circuit’s decision in Corporacion Mexicana de Mantenimiento Integral, S. de R.L. de C.V. v. Pemex-Exploracion y Produccion, 832 F.3d 92, 106 (2d Cir. 2016) (Pemex) was the only instance in which a federal appeals court had upheld a US court’s judgment enforcing an award that had been set aside by a court at the seat.

The dispute arose from a shareholder agreement between Compañía de Inversiones Mercantiles (CIMSA) and Grupo Cementos de Chihuahua (GCC), pursuant to which GCC acquired a 47% interest in Bolivian cement company Sociedad Boliviana de Cemento (SOBOCE). At that time of purchase, CIMSA was SOBOCE’s controlling shareholder. The shareholder agreement provided that, after five years, either party could sell its shares to a third party, subject to the other party’s right of first refusal to purchase the shares on the same or better terms. The agreement’s arbitration clause required that any dispute under the agreement be submitted to arbitration before the Inter-American Commercial Arbitration Commission (IACAC) in Bolivia, and the arbitration would be governed by Bolivian law.

When GCC sought to sell its shares to a third party, CIMSA exercised its right of first refusal and offered to purchase GCC’s shares on the same terms. GCC accepted CIMSA’s offer, but just before the transaction was set to close, GCC demanded additional collateral to secure payment of the purchase price under the agreed schedule. When CIMSA refused, GCC declared CIMSA’s offer invalid and sold its shares to the third party.

CIMSA initiated arbitration, claiming that GCC had violated CIMSA’s contractual right of first refusal. The tribunal issued a merits award for CIMSA holding GCC in breach of the shareholder agreement, and a separate damages award providing compensation to CIMSA for GCC’s breach. GCC sought annulment of the awards in Bolivian court, and CIMSA petitioned the United States District Court for the District of Colorado to enforce the damages award. Following procedurally complex actions in Bolivian courts, Bolivia’s highest court refused to annul the damages award. The District of Colorado subsequently entered judgment recognizing the award. After the US court issued its judgment, GCC again petitioned the Bolivian courts to annul the damages award, and a different chamber of Bolivia’s highest court, which had not been involved in the prior decision, issued an order annulling the award. GCC then returned to the District of Colorado, and moved under Federal Rule 60(b)(5) to vacate the district court’s earlier judgment enforcing the award. The district court denied GCC’s motion, finding that vacating its earlier judgment would offend US public policy. The Tenth Circuit affirmed.

The Tenth Circuit began its analysis by noting the unusual procedural posture of the case, where GCC both started a new annulment proceeding and obtained the Bolivian court’s annulment order after the district court had already entered judgment confirming the award. Given this posture, this case involved the confluence of Convention Article V(1)(e) and Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b) governing the courts’ power to relieve parties from the effect of final federal court judgments.

Ordinarily, courts will refuse enforcement of awards set aside at the seat (i.e., the “primary jurisdiction”) because “comity interests generally constrain a court from disregarding a primary jurisdiction’s annulment of an arbitral award.” US courts may only refuse to give effect to a foreign annulment order if doing so would violate a fundamental US public policy. This is a high threshold, which is met only where giving effect to the foreign judgment would be “repugnant to fundamental notions of what is decent and just in the United States.”

But, the court noted, revisiting a final judgment under Rule 60(b) is also “extraordinary relief” that may only be granted in “exceptional circumstances.” In deciding whether to undo a final judgment, the movant must not only show grounds for relief under Rule 60(b), but also why “its conduct, as a matter of equity, should allow vacatur.” And the district court has broad discretion to weigh the relevant factors in determining whether to vacate its prior judgment.

Applying these standards to the instant case, the Tenth Circuit found the district court acted within its discretion in refusing to afford comity to the Bolivian annulment order. This was because, although the court recognized that the Bolivian annulment order was not itself repugnant to US public policy, it found that giving “effect to” the Bolivian order and refusing enforcement of the award would violate three “strong” US public policy interests. These included protecting the finality of judgments, upholding parties’ contractual expectations, and the policy favoring arbitral dispute resolution. Focusing on the standard for vacating judgments under Rule 60(b), the court further emphasized how GCC’s “inequitable” conduct frustrated these fundamental policies.

The court was primarily focused on how giving effect to the Bolivian annulment order and vacating its prior judgment would violate the public’s “strong interest in protecting the finality of judgments.” At the time the district court entered judgment, Bolivia’s high court had already refused annulment. But GCC then went back to Bolivian courts to seek a new annulment order. Applying Rule 60(b), the court concluded that it was inequitable for GCC to wait until after the district court recognized the award to initiate new annulment proceedings in Bolivia, which militated against undoing the court’s final judgment. Emphasizing the point, the court distinguished this case from others that had refused to enforce awards that had been annulled at the seat, noting that “in every case affirming a district court’s decision not to confirm an arbitral award due to a foreign court’s annulment, the movant had sought annulment in the primary jurisdiction before confirmation of the arbitral award in the United States.”

The court then noted that vacating the judgment and refusing to recognize the award would also frustrate the strong policy in favor of upholding parties’ contractual expectations, particularly whereas here, the parties’ arbitration agreement provided that the parties “waive[d] all actions for annulment, objection, or appeal against that award.” Finally, and relatedly, refusing to enforce the award would also frustrate the “emphatic federal policy in favor of arbitral dispute resolution,” which “applies with special force in the field of international commerce.”

There was a dissent. According to the dissent, a foreign judgment should only be denied comity in the narrowest of circumstances, where it is “the judgment itself, or the processes that yielded it, that violates fundamental notions of decency and justice in the United States.” There being no question that the Bolivian annulment order itself was not repugnant to any strong US public policy, the dissent believed that the majority erred in declining to afford comity to the Bolivian order. In the dissent’s view, the majority was wrong to conclude that the mere fact that “giving effect” to an otherwise unobjectionable foreign judgment frustrated the US public policy favoring finality of judgments. This, the dissent argued, “suggests the presumption of comity yields to an easily satisfied ‘repugnancy’ standard,” which would be not only inconsistent with the decisions of other federal appellate courts, but “moves this court out of line globally with signatory countries.”

The case was not appealed to the Supreme Court, so it remains to be seen whether future disputes clarify whether the Tenth Circuit’s decision is truly out of step with the strong presumption of comity afforded foreign judgments, or whether it is a sui generis decision limited to its unique facts.

Read the court’s full decision here.

But court construed carveout merely to permit parties to seek court intervention in aid of arbitration and compelled arbitration.

Continental Materials, Inc. v. Veer Plasticas Private Limited, No. 22-cv-3685-MRP (E.D. Pa. April 4, 2023).

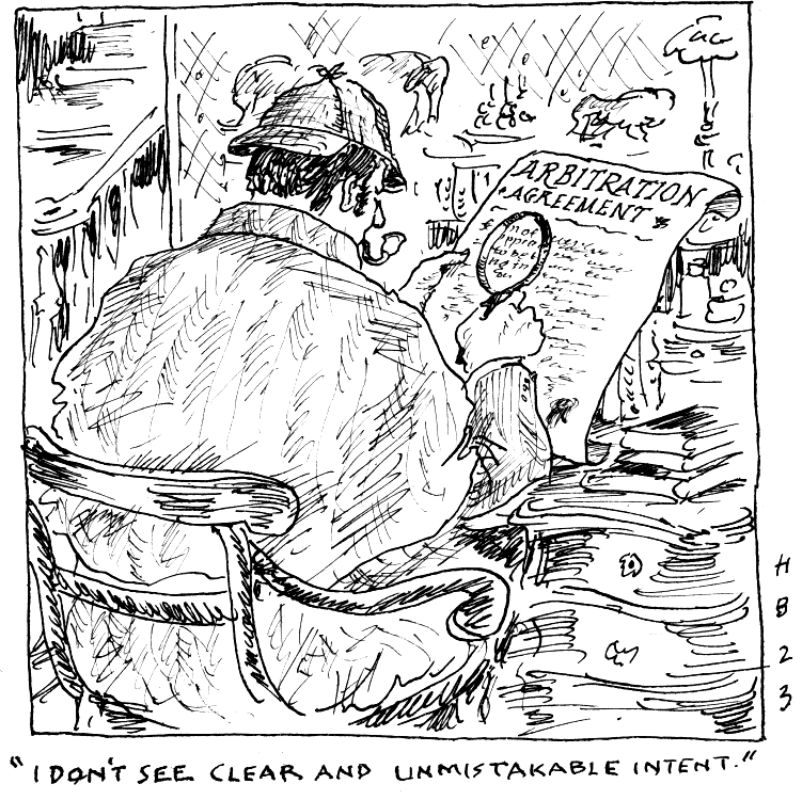

Whether a dispute falls within the scope of the parties’ arbitration agreement, often termed “arbitrability,” is a “gateway” issue that is presumptively for the court, rather than the arbitrators, to decide. However, where the parties have “clearly and unmistakably” agreed to arbitrate arbitrability, the question is for the arbitrators. The rules of many arbitral institutions, including the ICC rules, provide that arbitrators may determine their own jurisdiction, and courts have consistently held that the agreement to arbitrate under such institutional rules therefore constitutes clear and unmistakable intent to arbitrate arbitrability. In Continental Materials, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania recognized a narrow exception to this rule. Because the parties’ arbitration agreement arguably carved out a category of disputes from arbitration, whether the dispute falls within the carveout was for the court, notwithstanding the agreement to arbitrate under the ICC rules.

Whether a dispute falls within the scope of the parties’ arbitration agreement, often termed “arbitrability,” is a “gateway” issue that is presumptively for the court, rather than the arbitrators, to decide. However, where the parties have “clearly and unmistakably” agreed to arbitrate arbitrability, the question is for the arbitrators. The rules of many arbitral institutions, including the ICC rules, provide that arbitrators may determine their own jurisdiction, and courts have consistently held that the agreement to arbitrate under such institutional rules therefore constitutes clear and unmistakable intent to arbitrate arbitrability. In Continental Materials, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania recognized a narrow exception to this rule. Because the parties’ arbitration agreement arguably carved out a category of disputes from arbitration, whether the dispute falls within the carveout was for the court, notwithstanding the agreement to arbitrate under the ICC rules.

The underlying dispute in Continental Materials concerned a distribution agreement between Continental Materials, Inc. (CMI), a Pennsylvania roofing products company, and Veer Plastics, an Indian roofing products company. Under the agreement, CMI would distribute Veer’s products in North America, and would appoint a sales manager to “develop and facilitate new sales” of Veer’s products. The agreement prohibited Veer from soliciting or hiring CMI employees.

CMI hired Mark Hinterlong to serve as sales manager under the agreement with Veer. As a condition of his employment, Hinterlong signed a Confidential Information and Relationship Protection Agreement, which precluded him from disclosing CMI’s trade secrets and from accepting employment with CMI’s competitors or interfering with its vendor relationships for one year after the termination of his employment.

In August 2022, Hinterlong resigned from CMI. Shortly thereafter, he began working for Veer. CMI instructed Hinterlong to return his company-issued laptop, but before doing so Hinterlong provided the computer to Veer, who hired a third party to image the hard drive and delete information related to Veer. CMI then commenced suit against Veer in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, asserting various claims, including a claim for injunctive relief. Veer moved to compel arbitration under the arbitration clause in the parties’ distribution agreement.

Though the agreement required that “any dispute, controversy or claim between the parties” be settled by arbitration before the ICC in London, it further provided that “notwithstanding the foregoing, a Party may seek specific performance of this Agreement or any other equitable relief in a court of competent jurisdiction.” CMI argued that this carveout permitted any party seeking equitable relief to litigate its claims in court.

In deciding whether to compel arbitration, the court first determined that whether the carveout applied was a question for the court, not the arbitrators. The court noted that the burden of overcoming the presumption that courts decide arbitrablity was “onerous, as it requires express contractual language unambiguously delegating the question of arbitrability to the arbitrator.” The court recognized that a broad agreement to arbitrate any dispute coupled with designation of the ICC rules “tend to evince the parties’ intent to delegate questions of arbitrability to the arbitrators.” However, “the inclusion of a provision that at least arguably carves out” CMI’s claims “creates an ambiguity.” Accordingly, Veer did not meet its burden of demonstrating the parties’ “clear and unmistakable” intent to arbitrate arbitrability, and thus it was for the court to decide arbitrability.

But on the merits, the court held the dispute was arbitrable and granted the motion to compel. The most reasonable interpretation of the carveout was that it permitted the parties to seek equitable relief from a court only in aid of arbitration, such as “judicial enforcement of the arbitration agreement and of any award entered by the arbitrators.” This was because accepting CMI’s claim that the equitable relief carveout “broadly permits the parties to seek injunctive relief directly from any court” would permit a party to circumvent arbitration by merely including any claim for equitable relief. This “would create a carveout so broad that it would render the rest of the arbitration agreement void,” which would be “contrary to … the parties’ evidenced intent to send the disputes to arbitration.”

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.