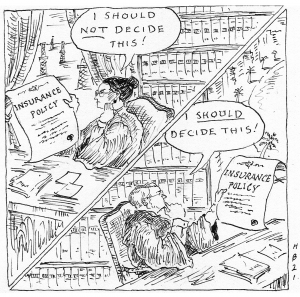

Decisions issued by the U.S. District Courts for the Southern District of Florida and Northern District of Texas reach seemingly inconsistent conclusions, increasing doubts about whether bankruptcy courts will handle disputes concerning a debtor’s insurance coverage.

District courts have long debated whether bankruptcy courts should exercise jurisdiction over disputes concerning a bankrupt estate’s insurance coverage. In some circuits, insurance coverage disputes are resolved in the bankruptcy court on the premise that resolution of those disputes significantly impacts the administration and property of the bankruptcy estate. Courts in other circuits withdraw the reference to the bankruptcy court primarily on the theory that insurance coverage disputes are non-core actions concerning state law issues rather than rights arising under federal bankruptcy law. This inconsistent approach continued when federal district courts in Florida and Texas diverged on whether bankrupt policyholders’ insurance coverage claims should be treated as core bankruptcy matters or run-of-the-mill state law coverage litigation.

District courts have long debated whether bankruptcy courts should exercise jurisdiction over disputes concerning a bankrupt estate’s insurance coverage. In some circuits, insurance coverage disputes are resolved in the bankruptcy court on the premise that resolution of those disputes significantly impacts the administration and property of the bankruptcy estate. Courts in other circuits withdraw the reference to the bankruptcy court primarily on the theory that insurance coverage disputes are non-core actions concerning state law issues rather than rights arising under federal bankruptcy law. This inconsistent approach continued when federal district courts in Florida and Texas diverged on whether bankrupt policyholders’ insurance coverage claims should be treated as core bankruptcy matters or run-of-the-mill state law coverage litigation.

By way of background, under 28 U.S.C. § 1334(a), federal district courts have “original and exclusive jurisdiction of all cases under Title 11,” i.e., all bankruptcy cases. That jurisdiction is not exclusive for three sub-categories within bankruptcy cases, i.e., civil proceedings: (i) “arising under” Title 11; (ii) “arising in” a case under Title 11; and (iii) “related to” a Title 11 case. Further complicating the situation is the fact U.S. bankruptcy courts are Article I courts whose jurisdiction over bankruptcy cases is delegated by U.S. district courts. That delegation occurs through a local rule or standing order in each district automatically referring to bankruptcy courts all cases under Title 11 and all proceedings arising under or in or relating to such cases.

Nonetheless, parties to bankruptcy cases, proceedings, and matters may, in limited circumstances, request the district court to withdraw the reference to the bankruptcy court on the grounds such withdrawal is either mandatory or permissive. Those requests sometimes are accompanied by requests for mandatory or permissive abstention by the district court. Whether the dispute at issue is “core” or “non-core” is central to such determinations. The core/non-core distinction also determines whether an Article I bankruptcy court may issue a final order, which may be done without the parties’ consent only in a core proceeding. Otherwise, absent the parties’ consent in a non-core proceeding, a bankruptcy court only may propose findings of fact and conclusions of law to the district court.

In In re American Resource Management Group, LLC (DE), 2020 WL 4217723 (S.D. Fla. July 23, 2020), two companies that manage time-share vacation homes – Wyndham and Bluegreen – sued American Resource Management Group (“ARMG”), a timeshare exit company, alleging it misled time-share owners into purchasing illusory “cancellation” or “transfer” services in order to “lawfully” terminate their agreements with Wyndham or Bluegreen. Id. at *1. According to Wyndham and Bluegreen, ARMG’s services consisted of sending letters threatening legal action on the time-share owners’ behalves and advising them to default on payments. Id. As a result, the time-share managers argued ARMG induced multiple owners to breach their contracts. Id. ARMG had sought coverage for the Wyndham and Bluegreen lawsuits from Scottsdale Insurance Company.

Once ARMG filed for chapter 11, its trustee sought a declaratory judgment that Scottsdale had a duty to defend ARMG. The insurer filed a motion to withdraw the reference of that litigation to the bankruptcy court, arguing: (1) the coverage dispute was a “non-core proceeding” because it does not “arise under” Title 11; and (2) judicial economy mandates that the district court determine the coverage dispute. Id. at *2. The district court began by noting that “core proceedings include those ‘arising under’ Title 11 or ‘arising in’ a case under Title 11, whereas non-core proceedings are those which are merely ‘related to’ a case under Title 11.” Id. The court acknowledged there is no bright-line rule that insurance coverage disputes are non-core proceedings. Still, the court held that because insurance proceeds are property of the debtor’s estate, coverage disputes are presumptively core proceedings. Id.

The district court also rejected Scottsdale’s argument to withdraw the reference in the interest of judicial economy. The district court reasoned the bankruptcy court was equally qualified to address insurance issues and the fact any appeal from a bankruptcy court decision would flow to the district court was inherent in the initial reference to the bankruptcy court. Id. at *3. Consequently, the district court held the dispute concerning the parties’ rights and obligations under the debtor’s insurance policy should be adjudicated by the bankruptcy court.

Just weeks later, a Northern District of Texas district court reached the opposite conclusion regarding core/non-core proceedings. In Boy Scouts of America v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co., 2020 WL 4530370 (N.D. Tex. Aug. 6, 2020), the policyholder Boy Scouts of America sought coverage from Hartford and related entities for sexual assault lawsuits. Initially, the Boy Scouts sought a declaratory judgment regarding coverage in a Texas state court and the insurers filed a notice of removal of that request to the federal district court. Id. at *1. Subsequently, the Boy Scouts filed a chapter 11 case in Delaware. Id. at *2. The Boy Scouts’ insurers then sought to transfer venue from the Texas district court to the Delaware district court, with the potential for automatic reference to the Delaware bankruptcy court handling the Boy Scouts’ chapter 11 case. The insurers asserted the district court had jurisdiction because the dispute was “related to” a chapter 11 case. Id. Meanwhile, the Boy Scouts sought mandatory or permissive abstention and a remand to the Texas state court. The Texas district court denied the insurers’ motion and held mandatory abstention required remanding the dispute to the Texas state court. Id.

In determining that mandatory abstention was appropriate, the Texas district court held that insurance coverage disputes are not core proceedings. The court reasoned that core proceedings are an integral part of a bankruptcy case involving a right created by federal bankruptcy law or that would arise only in bankruptcy. Id. at *9. In contrast, “related-to” matters are peripheral to a bankruptcy case and based on extrinsic sources of law, such that the dispute could exist outside of bankruptcy law. Id. The court reasoned that because insurance coverage disputes are based on state contract law, the disputes can be effectively resolved as ordinary breach of contract suits by state courts. Id. at *10. The court apparently did not believe the insurance-related issues were so intertwined with issues before the bankruptcy court that it should resolve those issues. Further, the court did not even consider the impact resolution of the insurance dispute might have on the bankruptcy estate.

These disparate views on how to handle insurance coverage disputes might result from the framework in which each dispute was analyzed and the advocacy of the parties. In Boy Scouts, the issue was considered narrowly in the context of 28 U.S.C. § 1334(b) and “related to” jurisdiction. In addition, the insurers did not forcefully press the argument that the dispute was a core proceeding. In contrast, in In re American Resource Management, the court’s focus was on whether the claims were property of, and would have an impact on, the bankruptcy estate. Additionally, the policyholder more aggressively argued that coverage disputes should be viewed as core proceedings. Regardless, the fact that the issue was decided differently only days apart confirms the uncertainty for parties litigating insurance coverage disputes in bankruptcy cases.

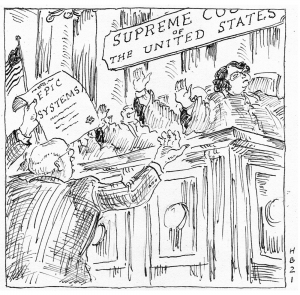

Petitioner argued lower court decisions failed to adhere to the Supreme Court’s “clear and manifest” standard for superseding the FAA’s “command of arbitration” and sought review of Second Circuit ruling denying arbitration of bankruptcy discharge order dispute.

On March 8, 2021, the Supreme Court declined to hear GE Capital v. Belton, a case addressing the relationship between the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”) and the United States Bankruptcy Code. In its petition for review, Synchrony Bank, f/k/a GE Capital Retail Bank, argued the Second Circuit Court of Appeals erred in In re Belton, 961 F.3d 612 (2d Cir. 2020), by holding an agreement to arbitrate in the bank’s credit card agreement was unenforceable in a dispute concerning an alleged violation of a bankruptcy court discharge order.

On March 8, 2021, the Supreme Court declined to hear GE Capital v. Belton, a case addressing the relationship between the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”) and the United States Bankruptcy Code. In its petition for review, Synchrony Bank, f/k/a GE Capital Retail Bank, argued the Second Circuit Court of Appeals erred in In re Belton, 961 F.3d 612 (2d Cir. 2020), by holding an agreement to arbitrate in the bank’s credit card agreement was unenforceable in a dispute concerning an alleged violation of a bankruptcy court discharge order.

The individual plaintiffs were two credit card debtors who brought claims on behalf of a putative class of chapter 7 debtors that previously held accounts managed by the bank defendants. The two plaintiffs had been chapter 7 debtors who obtained discharges of certain debts, including their outstanding credit card balances. Under section 524(a)(2) of the Bankruptcy Code, orders granting discharges operate as “injunction[s] against any future collection attempts.” In re Belton, 961 F.3d at 614. Plaintiffs alleged that notwithstanding the discharge orders, the credit card issuers improperly applied pressure on debtors to collect their discharged obligations by continuing to report the debts to credit agencies as “charged-off” (i.e., severely delinquent, but still outstanding) without noting the debts were discharged in bankruptcy. As a result, the plaintiffs reopened their chapter 7 cases and initiated adversary proceedings against the bank issuers to assert they had violated the discharge orders.

The banks moved to enforce mandatory arbitration clauses in their credit card agreements. The bankruptcy court denied the motion after finding application of the FAA to enforce the arbitration clauses would conflict with the Bankruptcy Code. The district court affirmed on appeal.

On further appeal, the Second Circuit agreed with the lower courts’ decisions. Based on Shearson/American Express, Inc. v. McMahon, 482 U.S. 220 (1987), the Second Circuit acknowledged the Federal “Arbitration Act requires courts to strictly enforce arbitration agreements. But like any statutory directive, that mandate may be overridden by contrary congressional intent . . . . Such an intent may be deduced from ‘the statute’s text or legislative history, or from an inherent conflict between arbitration and the statute’s underlying purposes.’” In re Belton, 961 F.3d at 615.

Although McMahon requires a court to examine the Bankruptcy Code for congressional intent, the Second Circuit noted it was not “writing on a blank slate,” but instead should be guided by the “nearly identical dispute” in Anderson v. Credit One Bank, N.A. (In re Anderson), 884 F.3d 382 (2d Cir. 2018), cert. denied 139 S. Ct. 144 (2018). In Anderson, the Second Circuit panel found “arbitration was in ‘inherent conflict’ with enforcement of a discharge order because (1) the discharge injunction is ‘integral’ to the bankruptcy process; (2) ‘the claim [concerns] an ongoing bankruptcy matter that requires continuing court supervision;’ and (3) ‘the equitable powers of the bankruptcy court to enforce its own injunctions are central to the structure of the Code.’” In re Belton, 961 F.3d at 615. The Belton panel concluded its “hands seem to be bound by that panel’s decision.”

The banks, however, argued the Second Circuit’s Anderson decision conflicted with the Supreme Court’s subsequent precedent in Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, 138 S. Ct. 1612 (2018) because there is no evidence in the Bankruptcy Code, let alone clear and manifest evidence, that Congress intended to displace arbitration for disputes regarding the discharge statute. In Epic Systems, the Supreme Court emphasized that “[a] party seeking to suggest that two statutes cannot be harmonized, and that one displaces the other, bears the heavy burden of showing ‘a clearly expressed congressional intention’ that such a result should follow.” 138 S. Ct. at 1624. Also under Epic Systems, Congressional intent must be “clear and manifest” and the statutory conflict “irreconcilable.” Id.

The Second Circuit rejected the banks’ position, reasoning that the test under Epic Systems is “substantially the same” as under McMahon, particularly as “Epic Systems never stated an intention to overrule McMahon.” In re Belton, 961 F.2d at 615-16. Instead, Epic Systems merely clarifies that when two of McMahon’s factors conflict, the statutory text should be utilized to resolve the dispute. See id. at 616. Further, while the Bankruptcy Code’s silence on overriding arbitration supports the absence of Congressional intent to do so, that is not determinative. Rather, the key is the “inherent conflict” between the Bankruptcy Code and arbitration. Id.

In its petition for certiorari, GE Capital contended that because the Second Circuit’s decision failed to apply the Supreme Court’s “clear and manifest” standard from Epic Systems, Supreme Court review was warranted. GE Capital’s petition was denied on March 8th, leaving open the Supreme Court’s view of the standard applicable to resolution of conflicts between the FAA’s preference for arbitration and the Bankruptcy Code. Presumably, it would require another circuit court’s opinion conflicting directly with Belton to elicit that determination.

Court upheld confirmed chapter 11 plan notwithstanding disparate treatment between certain classes of unsecured creditors because plan was substantially consummated and majority found the only potential relief would require overriding the plan. The concurring judge, however, argued the appellant’s proposed alternative individualized relief required serious consideration.

In In re Nuverra Environmental Solutions, Inc., 834 Fed. Appx. 729 (3d Cir. Jan. 6, 2021, amended Feb. 6, 2021), a divided Third Circuit panel upheld denial of an appellant unsecured creditor’s challenge to an implemented chapter 11 plan that discriminated between different classes of unsecured creditors. The majority opinion serves as a reminder of appellate courts’ willingness to dismiss appeals based on the doctrine of equitable mootness. Such courts are quite reluctant to modify substantially consummated chapter 11 plans if granting relief would require unwinding or “scrambling” the plan and/or significantly harming third parties who justifiably relied on the plan’s confirmation. The concurring opinion, however, questions the equitable mootness doctrine’s broad scope and suggests the need for greater analysis of a creditor’s unfair discrimination claim when individualized relief might be fashioned.

In 2017, oilfield logistics and equipment company Nuverra sought chapter 11 protection to address almost $600 million of outstanding liabilities, including approximately $500 million of secured debt, $40.4 million of unsecured notes, and an unspecified amount of unsecured trade obligations. Nuverra’s enterprise value was approximately $302.5 million, i.e., barely one-half of the debtors’ total liabilities. Under Nuverra’s reorganization plan, secured creditors would receive equity valued at approximately 54.5% of their secured claims and make a voluntary “gift” in the form of cash and stock to unsecured creditors who otherwise would not be entitled to a distribution under the Bankruptcy Code. The gift distinguished between two unsecured creditor groups: trade creditors would receive full payment of their claims while unsecured noteholders only would receive around 6% of their note claims.

The holder of $450,000 in unsecured notes (who would receive the lower 6% recovery under the plan) objected, arguing the plan improperly classified the note and trade creditors separately and, therefore, unfairly discriminated between such equally-ranked claims. As the class of unsecured note claims had rejected the plan, it only could be confirmed under section 1129(b) if the plan did not unfairly discriminate against the rejecting class. The U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware overruled the objection. The bankruptcy court reasoned the separate classification was reasonable rather than “unfair” because: (a) there was a clear distinction between unsecured trade claims arising from the debtors’ day-to-day operations and unsecured note claims; and (b) the debtors needed to maintain ongoing business relationships with their trade creditors to ensure the feasibility of future operations. Also, the bankruptcy court reasoned there was no unfair discrimination against the unsecured note holders because they were out of the money and absent the secured creditors’ “gift”, unsecured claims would not be entitled to any distribution under the Bankruptcy Code’s priority scheme.

While the unsecured noteholder’s appeal to the district court was pending and after denial of the appellant’s motion for a stay pending appeal, Nuverra consummated the plan. The district court then dismissed the appeal as “equitably moot,” invoking a doctrine courts use when granting the relief sought on appeal would require the unscrambling of a previously confirmed and implemented chapter 11 plan. The district court reasoned that granting the appeal would require undoing the plan to require payment to all unsecured noteholders because the alternative individualized relief sought by the appellant, payment in full of only his $450,000 of unsecured notes, would require prohibited disparate treatment of appellant’s claim from those of all other unsecured note claims in that class.

On further appeal, a split Third Circuit panel affirmed the district court’s decision. The majority characterized equitable mootness as a “narrow doctrine” that should be used when practicality so requires because the relief requested would “undermine the finality and reliability of consummated plans of reorganization.” When considering whether application of the doctrine was appropriate, the majority instructed courts to analyze: “(1) whether a confirmed plan has been substantially consummated; and (2) if so, whether granting the relief requested in the appeal will (a) fatally scramble the plan and/or (b) significantly harm third parties who have justifiably relied on plan confirmation.”

The majority reasoned that paying all unsecured noteholders in full was not possible because the plan had been substantially consummated and relief would require scrambling the consummated plan. The majority also found that mandating modification of the plan solely to require paying the appellant in full was prohibited by (a) Bankruptcy Code section 1123(a)(4)’s requirement that all claims in a class receive equal treatment unless the holder thereof agrees to less favorable treatment; and (b) Bankruptcy Code section 1129(b)(1)’s prohibition on unfair discrimination not being available to warrant relief here because the section is applicable only to classes of creditors, not to creditors individually. Consequently, the Third Circuit majority affirmed the district court’s dismissal on grounds of equitable mootness.

The most intriguing part of the opinion, however, is the concurring judge’s position that the individualized relief the appellant sought precluded dismissal of the appeal because it implicated neither of the rationales for equitable mootness. In effect, the requested relief would neither fatally scramble the plan nor significantly harm third parties who had justifiably relied on the plan’s finality. Thus, the concurring judge would have required “careful consideration” of whether the fact no other unsecured noteholder objected to the plan signified such other noteholders had “agreed to less favorable treatment” under section 1129(a)(4) and, therefore, granting payment in full to the single appealing unsecured noteholder was not precluded by that section. Similarly, the concurring judge asserted the other unsecured noteholders’ failures to appeal meant they had waived the unfair discrimination argument underlying the appeal. Consequently, even though this unpublished opinion lacks precedential standing, these novel arguments might be replicated in other appeals that draw a three judge bench more open to their consideration.

Meanwhile, the boundaries of the equitable mootness doctrine will continue to be tested. Hence, at a minimum, Nuverra serves as a reminder that plan opponents should quickly seek to preserve the possibility of effective judicial relief, including by obtaining a stay of consummation pending appeal and by identifying any forms of possible satisfactory relief that do not involve unscrambling a plan.

Marcel Engholm Cardoso, Legal Consultant

Hank Blaustein

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.