On remand, SDNY holds facultative reinsurer liable for defense costs in excess of indemnity limits.

Global Reins. Corp. of Am. v. Century Indem. Co., 13 Civ. 6577 (LGS) (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 2, 2020).

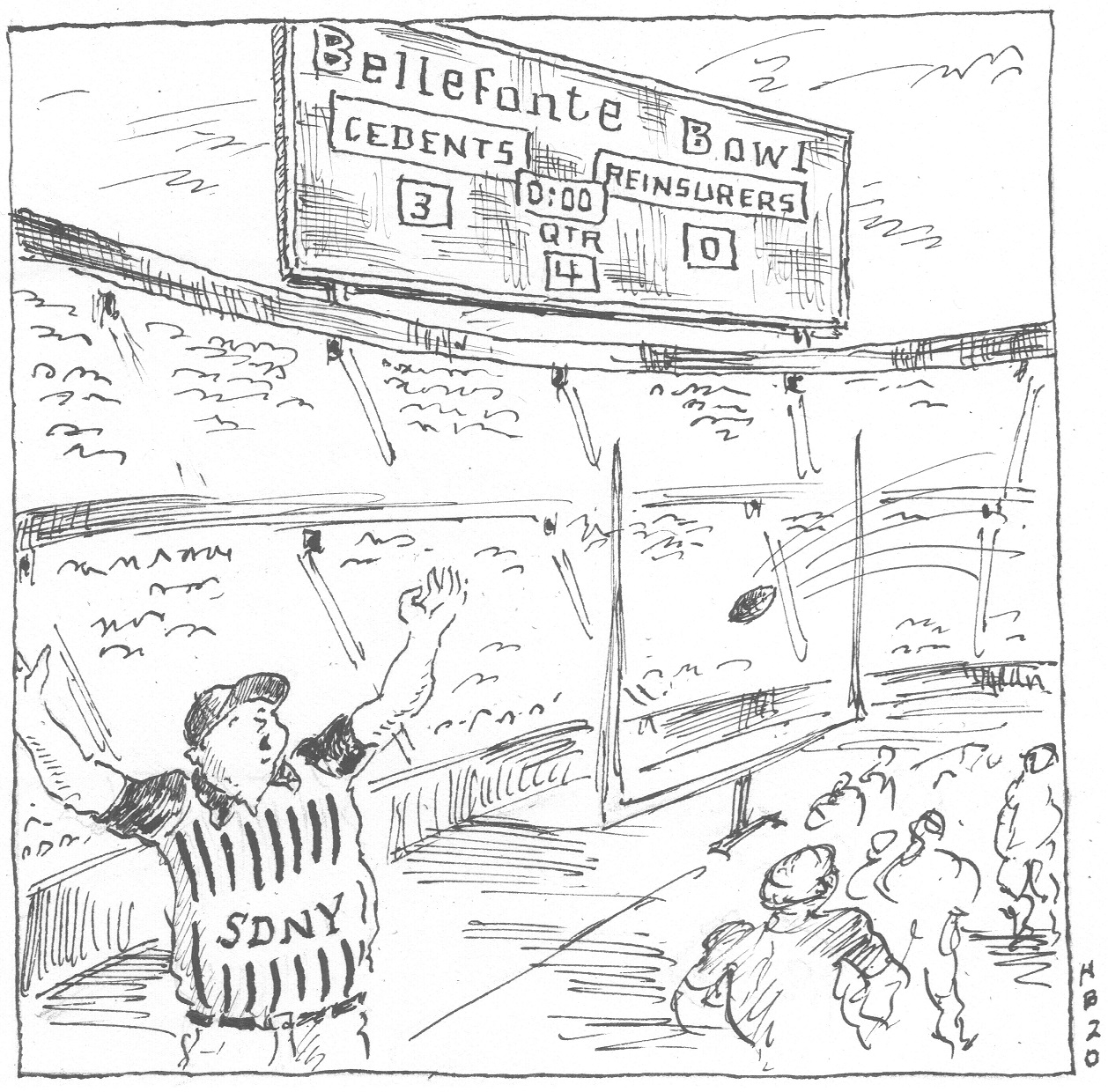

Thirty years ago, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decided, in Bellefonte Reinsurance Co. v. Aetna Cas. & Sur. Co., 903 F.2d 910 (2d Cir. 1990), that the limits of liability stated in a facultative reinsurance certificate cap the reinsurer’s liability for both indemnity and defense costs. Although the Bellefonte rule was criticized, for years it stood as an obstacle to complete reinsurance recovery for cedents whose policies required them to pay defense costs in addition to limits.

Thirty years ago, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decided, in Bellefonte Reinsurance Co. v. Aetna Cas. & Sur. Co., 903 F.2d 910 (2d Cir. 1990), that the limits of liability stated in a facultative reinsurance certificate cap the reinsurer’s liability for both indemnity and defense costs. Although the Bellefonte rule was criticized, for years it stood as an obstacle to complete reinsurance recovery for cedents whose policies required them to pay defense costs in addition to limits.

As we have previously reported, in Global v. Century, multiple courts have been deconstructing Bellefonte step-by-step. The first step took place in the Second Circuit, which reversed the district court’s decision based on Bellefonte and its progeny, pointedly questioning Bellefonte’s validity. 843 F.3d 120 (2d Cir. 2016) (discussed in Volume 2). Rather than overruling Bellefonte, however, the Second Circuit certified the question to the New York Court of Appeals. In the second step, the Court of Appeals responded that reinsurance contracts are to be interpreted under ordinary contract law principles, and that there is no special Bellefonte rule under New York law. 30 N.Y.3d 568 (2017) (discussed in Volume 3). The Second Circuit then remanded the case to the district court to interpret the specific facultative contracts at issue. 890 F.3d 74 (2d Cir. 2018).

The district court has now issued its decision on remand. In this latest chapter, the district court concluded that the reinsurance limit did not cap the reinsurer’s obligation to cover defense costs when the cedent pays both indemnity and defense costs. However, opining on an issue that was arguably unnecessary to its decision, the court also stated that the reinsurance limit does cap the reinsurer’s obligation to pay defense costs when the cedent pays only defense costs.

The court based its decision on the language of the reinsurance contracts, interpreted in light of expert testimony regarding industry custom and practice at the time the reinsurance was placed in the 1970s. It found that the “plain and unambiguous meaning of the reinsurance contracts is that the dollar amount stated in [the certificates] caps Global’s obligation to pay losses and also caps Global’s obligation to pay expenses when there are no losses, but does not cap Global’s obligation to pay expenses when there are losses.”

The court first noted that the reinsured policies contained a “Supplementary Payments” provision requiring Century to pay defense costs in addition to the stated policy limits. The Court then focused on two provisions of the reinsurance certificates. First, the “Follow Form Clause” provided that the reinsurer’s liability “shall be subject in all respects to all the terms and conditions of” the underlying Century policies, except when otherwise provided in the facultative certificates. Second, the “Payments Provision” stated, “In addition [to loss payments], the Reinsurer shall pay its proportion of expenses [including defense costs] … in the ratio that the Reinsurer’s loss payment bears to the Company’s gross loss payment.” That provision further provided that, “[i]f there is no loss payment, the Reinsurer shall pay its proportion of such expenses only in respect of business accepted on a contributing excess basis and then only in the percentage stated in” the certificate.

Taken together, these provisions meant that where Century paid both losses and defense costs under the reinsured policies, Global was obligated to cover defense costs in excess of the liability limit equal to its proportional share of the loss. On the other hand, where Century paid only defense costs, the court read the “Payments Provision” to cap the reinsurer’s liability for defense costs. Because Century had, in fact, paid both losses and defense costs, the court granted summary judgment for Century, finding that it was entitled to recover a proportional share of defense costs in excess of the liability limits.

Read the court’s full decision here.

Reinsurer was not bound by settlement that stipulated that missing primary policies contained aggregate limits where reinsured umbrella policies provided there were no aggregate primary limits.

Reinsurer was not bound by settlement that stipulated that missing primary policies contained aggregate limits where reinsured umbrella policies provided there were no aggregate primary limits.

Utica Mutual Ins. Co. v. Fireman’s Fund Ins. Co., 957 F.3d 337 (2d Cir. 2020).

Reinsurance contracts commonly include a “follow-the-settlements” clause, which, as the Utica Mutual court explained, binds the reinsurer to the cedent’s coverage determinations, “so long as the settlement decision was made ‘in good faith, reasonable, and within the terms of the applicable policies.’” Utica Mutual highlighted an important limitation on the follow-the-settlements principle – “a follow-the-settlements clause ‘does not alter the terms or override the language of the reinsurance policies.’” The Second Circuit reversed a jury verdict awarding Utica Mutual $65 million, holding, as a matter of law, that Utica’s settlement with its insured did not bind its facultative reinsurer, Fireman’s Fund Ins. Co., because the settlement contradicted the plain terms of the underlying policies, as incorporated into the reinsurance contracts.

From 1966 to 1972, Utica issued primary and umbrella policies to Goulds Pumps Co. Utica obtained facultative reinsurance for each of the umbrella policies from Fireman’s Fund. The reinsurance contracts contained a follow-the-settlements clause, as well as a “follow-the-form” clause effectively incorporating the terms of the umbrella policies into the reinsurance contracts.

Goulds received numerous bodily injury claims arising from exposure to asbestos, and sought coverage from Utica under the primary and umbrella policies. Because the primary policies were lost, it was unclear whether they included aggregate limits for bodily injury. This was important because most of the bodily injury claims did not exceed the per person or per accident limits in the primary policies. Thus, whether the primary policies were subject to aggregate limits determined whether the reinsured umbrella policies were triggered. Utica and Goulds eventually settled their coverage dispute, stipulating that the missing primary policies contained aggregate limits, that those limits had been exhausted, and thus that the umbrella policies reinsured by Fireman’s Fund had been triggered.

When Fireman’s Fund denied coverage, Utica commenced suit. Utica argued that, under the follow-the-settlements clause, Utica’s agreement with Goulds that the missing primary policies contained aggregate limits bound Fireman’s Fund. Fireman’s Fund countered that, among other things, the settlement was contrary to the terms of the umbrella policies, as incorporated into the reinsurance contracts. In particular, the umbrella policies provided that Utica “shall be liable only for the ultimate net loss … in excess of . . . the amounts of the applicable limits of liability of the underlying insurance as stated in the Schedule of Underlying Insurance Policies.” The Schedule in the umbrella policies included aggregate limits for property damage, but said nothing about aggregate limits for bodily injury.

The trial court denied Fireman’s Fund’s multiple motions for judgment as a matter of law that the reinsured umbrella policies were not triggered. Following a two-week trial, the jury returned a verdict for Utica. The court then entered judgment for Utica for principal and prejudgment interest of approximately $65 million.

The Second Circuit reversed. It found that the district court should have entered judgment as a matter of law for Fireman’s Fund because the umbrella policies unambiguously provided that they attached only in excess of primary policies that did not contain aggregate limits. Therefore, the losses that Utica and Goulds allocated to the reinsured umbrella policies fell outside the terms of the policies and the reinsurance contracts as a matter of law.

Importantly, the court noted that it “did not ignore relevant follow-the-settlements authority.” Rather, the court explained that its “decision is congruent with a continuous line of authority establishing that, to trigger deference under the follow-the-settlements doctrine, the settlement decision in question must be reasonable and in good faith but must also be within the terms of the reinsured policy.”

Full disclosure: Chaffetz Lindsey represented Fireman’s Fund before the Second Circuit.

Read the court’s full decision here.

No allocation issue arises when property damage was not progressive, but occurred at a fixed, discernable time.

Lubrizol Advanced Materials, Inc. v. Nat’l Union Fire Ins. Co. of Pittsburgh, PA, No. 2018-1815 (Ohio Apr. 23, 2020).

When property damage or bodily injury develops progressively over a number of years, as can be the case with some asbestos or environmental losses, the progressive damage or injury may trigger multiple liability insurance policies issued across the years of injury. Ultimately, all insurers that issued policies triggered by such progressive loss will typically be required to share in the loss based on their relative shares of exposure. However, the question often arises in these scenarios whether the insurers’ liability to the insured is several, in which case the insured must pursue a separate claim against each insurer for each insurer’s pro rata share of coverage. Alternatively, each insurer’s liability to the insured may be joint and several, such that the insured can seek coverage for its full loss (up to policy limits) under any triggered policy year. In that case, it is up to the insurers to spread the loss pro rata through contribution claims.

As with most issues, this question cannot be answered in the abstract because the specific policy language controls. But Ohio courts have previously ruled on the issue in connection with CGL policy language requiring the insurer to pay “all sums” arising from bodily injury or property damage during the policy period. The Ohio Supreme Court has held that such “all sums” language can, subject to all the terms of the policy, render multiple insurers jointly and severally liable to the insured (up to policy limits) for the same progressive loss, even if some of that loss occurred outside a particular insurer’s term of coverage. Insurers who face such joint and several liability, and who thereby discharge in whole or part the coverage obligations of other insurers, can then seek contribution from those other carriers.

But what if the policy provides that the insurer will pay “those sums” arising from bodily injury or property damage during the policy period? Is “those sums” narrower than “all sums”? That was the question presented to, though not conclusively answered by, the Ohio Supreme Court in the Lubrizol case.

Between 2001 and 2008, Lubrizol manufactured and sold allegedly defective resin to a customer, IPEX. IPEX used Lubrizol’s resin to make pipes, which it then sold to its consumers. When the pipes failed, IPEX settled a number of claims against it and sued Lubrizol. Lubrizol settled with IPEX and sought coverage from National Union under an umbrella policy issued in 2001. Lubrizol argued that it was entitled to coverage under the National Union policy for all of its losses under Ohio’s “all sums” allocation rule, even though the policy used the term “those sums,” and not “all sums.” After Lubrizol sued National Union in federal district court in Ohio, the federal court certified to the Ohio Supreme Court the following question:

Whether an insured is permitted to seek full and complete indemnity, under a single policy providing coverage for “those sums” the insured becomes legally obligated to pay because of property damage that takes place during the policy period, when the property damage occurred over multiple policy periods.

In essence, the question before the court was whether the “all sums” allocation method should also be applied to policies with “those sums” language.

The court determined, however, that it need not decide whether the “those sums” language required application of “all sums” allocation. No allocation rule, “all sums” or otherwise, could apply to Lubrizol’s loss because the issue of allocation only arises where property damage or bodily injury stems from ongoing “progressive injury.” In this case, Lubrizol did not prove that a progressive loss triggered multiple policies. Although Lubrizol incurred losses in different policy periods, the specific date of each injury was discernable. Specifically, the parties could determine how much resin was produced on a given date, how much was sold to IPEX, when the relevant lots of plumbing were produced, sold, and installed, and when they failed. Accordingly, the court held that the “operative contract language is not the reference to policy coverage for ‘those sums’ but rather to injury or damage ‘that takes place during the policy period.’” Because the injuries occurred at discernable times, there was no reason to use any methodology to allocate liability across multiple insurers and policy periods.

The court did, however, comment on the specific import of the “those sums” language. The court returned to first principles. Insurance policies are contracts. Thus, the court remarked, “[a]s with any contract, insurance policies should be interpreted as written, and the meaning of the phrase ‘those sums’ depends on the context of each policy and each case.” The court therefore declined to “set a bright line rule based merely on a party’s use of the word ‘those’ instead of ‘all.’”

Notably, three of the seven judges joined in a concurring opinion, which went one step further. The concurring judges concluded that the “those sums” language would unambiguously preclude an “all sums” allocation. They would have found that, “[w]hen a contract provision says that an insurer is required to pay only ‘those sums’ that arise from damage that occurs ‘during the policy period,’ that is all the insurer may be required to pay.” Moreover, and perhaps calling into question some of the earlier Ohio decisions in this area, the concurrence also noted that the clear difference in meaning between “those sums” and “all sums” made it unnecessary for the court to address in this case the “continuing vitality” of the court’s prior “all sums” rulings.

Read the court’s full decision here.

Court applies “unavailability exception” limiting allocation to years in which coverage was purchased or otherwise available in the market.

Rossello v. Zurich Am. Ins. Co., No. 24, September Term, 2019 (Md. Apr. 3, 2020).

In another state high court decision addressing the allocation of long-tail losses from progressive injuries, the Maryland Court of Appeals held – following a line of prior holdings from the State’s intermediate appellate court – that pro rata allocation applies in determining coverage for liability arising from progressive property damage or bodily injury. Under “pro rata” allocation, the insured can only recover from each insurer the portion of the loss corresponding to the insurer’s time on the risk.

The case arose after Rossello was diagnosed in 2013 with mesothelioma caused by his exposure to asbestos beginning in 1974. Lloyd E. Mitchell, Inc. (Mitchell) installed the asbestos while performing construction at Rosello’s workplace. After Rossello obtained a judgment against Mitchell, he obtained a writ of garnishment against Mitchell’s insurer, Zurich, which had issued CGL policies to Mitchell between 1974 and 1977. The court stayed garnishment pending resolution of Zurich’s coverage obligations.

Zurich argued, and the court agreed, that Rossello’s damages should be allocated on a pro rata time-on-the-risk basis across all insurable periods during which Rossello was exposed to asbestos. Notably, however, the court also adopted what is commonly referred to as the “unavailability exception,” which limits allocation to years in which coverage was purchased or otherwise available in the market. That is, although the insured is generally allocated the pro-rated share of loss corresponding to periods of no coverage, if the gap in coverage is due to the fact that insurance was not commercially available, then such periods of unavailability do not factor into the pro rata allocation.

The court found that the burden to prove that coverage was unavailable falls on the insured or claimant. In this case, however, Zurich acknowledged that 1985 was the final year that Mitchell would have been able to purchase coverage for asbestos liabilities, and Rossello did not prove otherwise. The court therefore held that the relevant period for allocation was twelve years – from Rosello’s initial exposure in 1974 until the final year insurance was available in 1985 – and that Zurich was liable only for its four-year pro rata share.

Stay informed of Chaffetz Lindsey’s updates, new articles, and events invitations by subscribing to our mailing list.