NY Commercial Litigation Report, July 2024

(Vol. 16)

Caveat emptor: Foreign purchasers of corporate assets may inherit their seller’s jurisdictional exposure

Court of Appeals: Where one foreign corporation acquires all the assets and liabilities of another, courts may exercise long-arm jurisdiction over the purchaser based on the seller’s New York acts.

Lelchook v. Société Générale de Banque au Liban SAL, 2024 WL 1661460 (N.Y. Apr. 18, 2024).

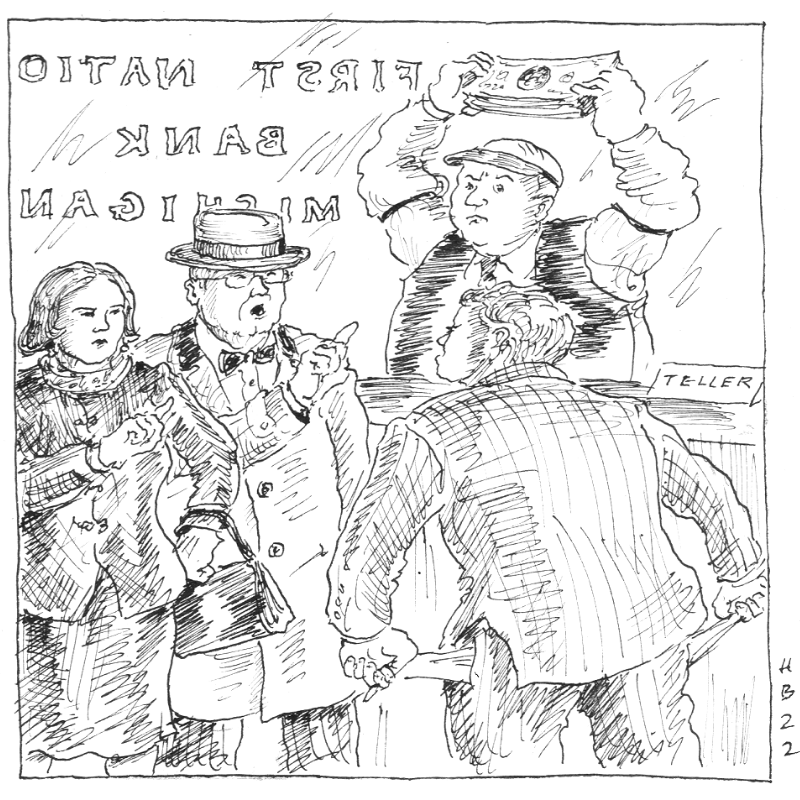

New York’s long-arm statute, CPLR 302, authorizes New York courts to exercise specific personal jurisdiction over non-domiciliaries where the defendant has engaged in certain enumerated acts, such as transacting business, or committing a tortious act, in New York and the plaintiff’s cause of action arises from those acts. Where a corporate defendant is the product of a statutory or de facto merger, a plaintiff may establish personal jurisdiction under CPLR 302 by imputing the predecessor corporation’s acts to the defendant.

The Court of Appeals held that this same rule applies where a corporate defendant “acquires all of another entity’s liabilities and assets, but does not merge with that entity.” If so, the court explained, “the seller corporation’s New York acts may be imputed to the defendant-purchaser.” Stated differently, the purchaser “inherits the acquired entity’s status for purposes of specific personal jurisdiction.” But this rule applies only where the purchaser acquires the entirety of the seller’s assets and liabilities. For example, “the purchase and continuation of a product line” will not expose the acquirer to jurisdiction in New York based on the seller’s prior acts.

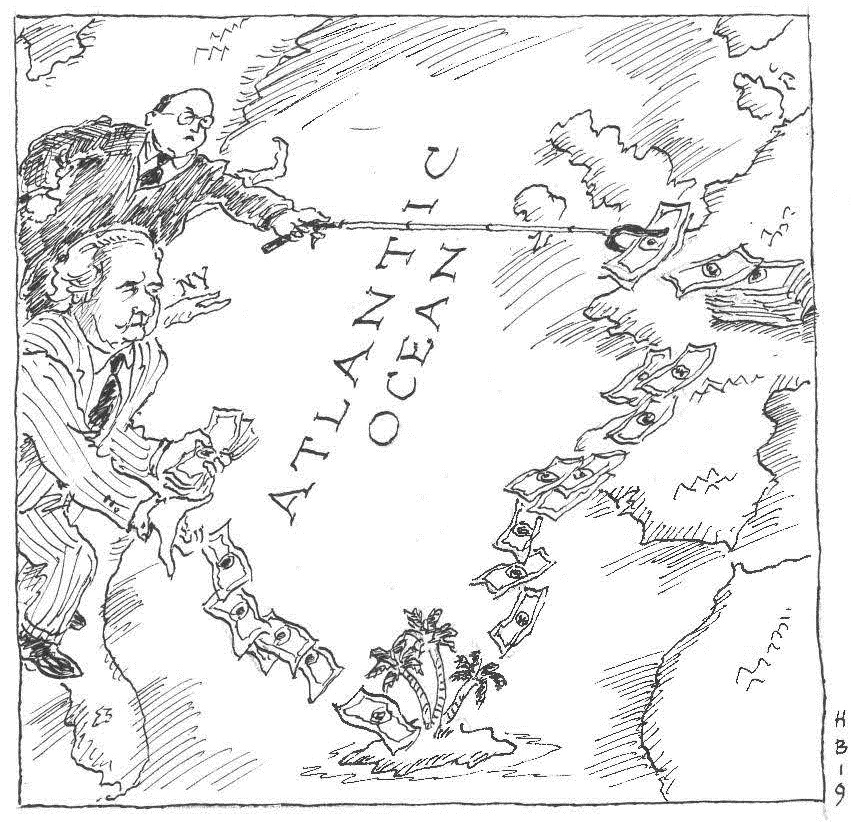

In 2008, a group of plaintiffs injured by Hizbollah rocket attacks in Israel sued the Lebanese Canadian Bank (“LCB”) in federal district court. Plaintiffs alleged that LCB provided financial assistance to Hizbollah, including wire transfers through a New-York based correspondent bank, thus subjecting it to specific personal jurisdiction in New York. Later, in June 2011, Société Générale de Banque au Liban SAL (“SGBL”) acquired “all of [LCB]’s Assets and Liabilities.” Later still, in 2019, plaintiffs brought similar claims against SGBL as LCB’s successor. The district court dismissed the claims against SGBL for lack of personal jurisdiction, but the Second Circuit certified the inherited jurisdiction question to the Court of Appeals.

The Court gave decisive weight to the expectations of the transacting parties and the rights of those injured by the predecessor corporation’s acts. “Sophisticated corporate entities,” the Court reasoned, “will undoubtedly engage in robust due diligence before agreeing to acquire all assets and liabilities of another entity” and “should understand where jurisdiction over such liabilities may lie and the potential cost if ultimately found liable.” And, at the same time, imputing the seller corporation’s acts to the acquirer would protect the interests of those injured by the seller’s acts: “Allowing a successor to acquire all assets and liabilities, but escape jurisdiction in a forum where its predecessor would have been answerable for those liabilities, would allow those assets to be shielded from direct claims for those liabilities in that forum.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

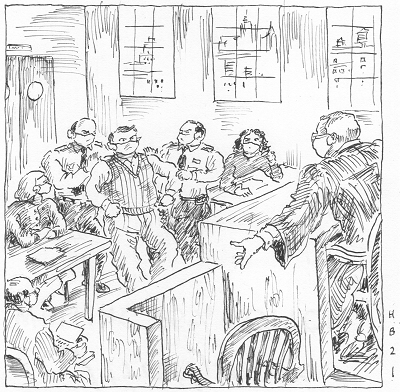

London (Margin) Calling: British Retailer’s Effort to Obtain Section 1782 Discovery from Morgan Stanley CEO Fails

Second Circuit: District court did not exceed its discretionary authority in denying plaintiff’s § 1782(a) discovery request on grounds of inefficiency and inconvenience.

Frasers Group PLC v. Stanley, 95 F.4th 54 (2d Cir. 2024).

28 U.S.C. § 1782 grants federal district courts discretion to order domestic discovery in aid of a foreign proceeding. Courts exercise this discretion by considering four overarching factors the United States Supreme Court identified in Intel Corp. v. Advanced Micro Devices, Inc., 542 U.S. 241 (2004): whether the discovery is sought from a participant in the foreign proceeding; the nature of the foreign tribunal and its receptivity to U.S. judicial assistance; whether the request is an attempt to circumvent a foreign jurisdiction’s proof-gathering restrictions; and whether the request is “unduly intrusive or burdensome.”

Frasers, a British retailer group, commenced English proceedings against Morgan Stanley & Co. International PLC (“MSIP”) to recover damages relating to a margin call. Two years into the proceedings, Frasers sought section 1782 discovery from James Patrick Gorman, the then-CEO of Morgan Stanley, who was located in the United States. While the statutory requirements were met, the district court denied the application on the grounds that the first and fourth Intel requirements weighed heavily against authorizing discovery. Frasers appealed, arguing the district court had abused its discretion by improperly requiring that all discovery mechanisms in the foreign venue be exhausted and denying the application merely because there were alternative means of procuring the materials sought.

The Second Circuit disagreed and affirmed the district court’s ruling. Under the first Intel factor, the need for Section 1782 discovery is not “apparent” where the discovery target is a participant in the foreign proceeding. Although Frasers sought documents from Gorman in the United States, the Second Circuit found Frasers was “for all intents and purposes” seeking documents from MSIP. The court relied on the concession that Frasers would be able to seek the same documents from Gorman, as CEO of MSIP’s parent, in the English proceedings.

The fourth Intel factor, which protects against “unduly intrusive or burdensome” requests, also led the Second Circuit to affirm the district court’s denial of discovery. Gorman’s documents could be obtained in the foreign proceeding, and his testimony “bore little relevance to Frasers’s claims” and was unduly burdensome when weighed against “his competing obligations as the Chief Executive Officer of Morgan Stanley.”

Read the court’s full decision here.

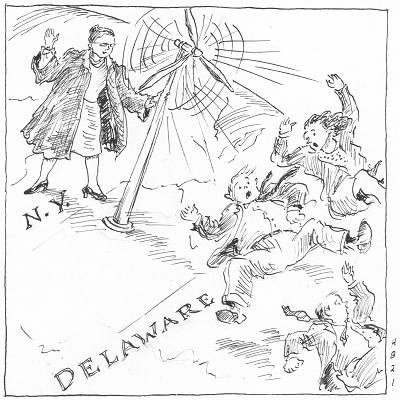

Homeward Bound: Scots Law Governs Suit Arising from Internal Affairs of Scottish Company

Court of Appeals: In a dispute arising from a company’s internal affairs, the law of the state of incorporation applies unless the state’s interest is “minimal” and New York’s interest is “dominant.”

Eccles v. Shamrock Capital Advisors, 2024 WL 2331737 (N.Y. May 23, 2024).

Under the “internal affairs doctrine,” in disputes arising from a company’s internal affairs, the law of the state of incorporation generally applies. But sometimes, a foreign company’s contacts with New York are so significant that New York law applies. On that basis, New York law applies only where “(1) the interest of the place of incorporation is minimal—i.e., [where] the company has virtually no contact with the place of incorporation other than the fact of its incorporation, and (2) New York has a dominant interest in applying its own substantive law.”

Plaintiffs, a group of common shareholders in FanDuel Ltd, an online fantasy sports company, claimed that a merger between FanDuel and Paddy Power Betfair plc, a sports betting firm, wrongfully divested them of their interest in FanDuel without compensation. Under the merger agreement, FanDuel would dissolve in the merger, and its shareholders would receive compensation in the form of equity in the new entity. The amount of equity received would be based on an agreed valuation of FanDuel. But, Plaintiffs alleged, FanDuel’s directors and certain preferred shareholders wrongfully deflated the company’s agreed valuation. As a result, when the merger closed, there was only enough equity to compensate FanDuel’s preferred shareholders. Plaintiffs, the common shareholders, lost their stake and received nothing.

Plaintiffs brought tort claims for breach of fiduciary duty under New York law against the directors and preferred shareholders. Defendants moved to dismiss, arguing that Scots law, not New York law, applied to plaintiffs’ claims and that plaintiffs had failed to state a claim under Scots law.

Determining whether Scots or New York law applied, the Court of Appeals began by “clarify[ing]” that “the substantive law of a company’s place of incorporation presumptively applies to causes of action arising from its internal affairs” (and not merely those involving corporate governance). Applying the two-pronged test described above, the Court of Appeals determined that the interest of Scotland was not “minimal.” FanDuel was founded in Scotland, registered under Scots law, its Articles of Association referenced Scots law, it maintained offices in Scotland, and many of the plaintiffs lived there. Nor was New York’s interest “dominant”—even though FanDuel had its principal office in New York, held board meetings in New York, and negotiated the merger in New York. Taking judicial notice of Scots law, the Court of Appeals held that plaintiffs met their burden to plead a legally cognizable claim under New York’s liberal pleading standard and allowed the case to proceed.